Environmental inequalities

PDF

Environmental inequalities are now a terminology that is increasingly used by civil society and politicians. But what exactly do these inequalities overlap? Are they only the result of the superposition of socio-economic inequalities already widely studied with specific environmental problems (exposure to industrial or natural risk, to nuisances; difficult access to environmental amenities…)? Do they require a new look at environmental issues and therefore specific action modalities? This article seeks to shed light on this theme, which is gradually being incorporated into social reflections and public action. To do this, it highlights the causes of these inequalities, then formulates a classification that makes it possible to expand their definition. Some modalities of repair are finally presented.

1. How to define environmental inequality?

Inequality is a relatively well understood concept; it illustrates the difference in access to and use of scarce and valued resources among individuals or social groups. This difference in situation between individuals or groups may be related to the resources they hold (education, income, social and cultural capital, etc.) or to their position in society (housing, employment situation, etc.). This is a social inequality. Since inequality can be embedded in space, we will then speak of spatial (or territorial) inequalities: some places do not benefit from the same services, the same economic dynamics as others, such as in digital access, where even today in France rural areas do not have access to the same services as urban areas.

Environmental inequalities intersect three dimensions: social, territorial and, of course, environmental. More concretely, environmental inequalities are the expression of an environmental burden that would be borne primarily by disadvantaged and/or minority populations or by territories suffering from a certain poverty and exclusion of these inhabitants. However, be careful: being subjected to a risk or pollution does not systematically lead to environmental inequality.

This is the case if this situation is suffered – and sometimes unknown – by the individual or population, not modifiable or amendable by the population or individual. This is also the case if it concerns more particularly a population/territory whose socio-demographic structure shows economic, social or political vulnerability (Coverage Figure ).

To understand the concept, a multidisciplinary analysis combining expertise in the human and social sciences, environmental sciences and citizen knowledge is necessary. This article aims to answer three questions: how do environmental inequalities arise? How to define and distinguish them? How are we trying to fight them and reduce them? Finally, are we facing new socio-environmental processes here or is this a new perspective on situations of social and environmental disadvantage?

Environmental inequalities are built on the basis of several processes that can act alone or in combination. They “do not result from a natural determinism that would affect a human population deemed homogeneous [1]“, nor from a social determinism.

One of the main causes is the lack of coverage of negative externalities by the person who creates them (developer, infrastructure operator, plant operator, waste exporting country, etc.) and by the person who benefits from the service and/or production derived from a polluting, risky and/or harmful activity. In this case, the effects of pollution emitted by an actor are not covered by the actor. The social cost is passed on to the individual who suffers its consequences (on his health, on the value of the property he may own, on the negative representation of his place of residence) and partly on society, since the latter must bear certain costs to protect citizens or reduce the impacts through appropriate measures. For example, an episode of air pollution that lasts too long causes an increase in breathing difficulties among vulnerable people, particularly asthma attacks. Children, the elderly and others will therefore suffer more and use health services more to treat themselves [2].

Let us take the example of an airport such as Roissy Charles de Gaulle. As a European hub, it offers a transport service for French travellers, tourists and a large number of transit passengers. Paris and the rest of France benefit from the flow of tourists thanks to him. The Ile-de-France region and the departments in which it is located are seeing the development of a number of economic activities. However, these beneficial effects do not always affect the areas closest to airports, particularly in terms of employment. Even more so, these local areas concentrate the negative effects and are poorly compensated since the positive effects are more widely distributed [4].

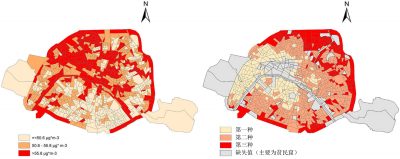

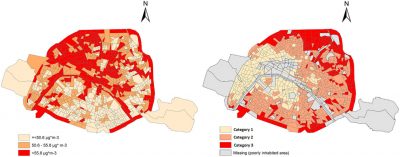

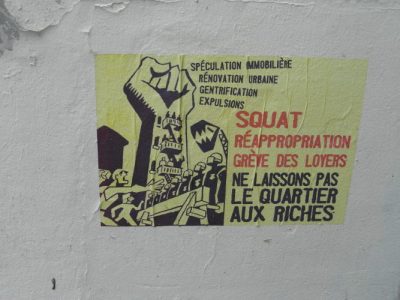

Similarly, planning practices [5] can encourage the emergence and entrenchment of strong environmental inequalities. Racial segregation in the American context has left a strong imprint: black-American neighbourhoods are distinct from neighbourhoods inhabited by “whites”. Segregation has flourished through urban planning regulations and investment choices, deriving from a long history of “urban marginalization” and racialization of behaviour (bankers, urban planners, local communities, individuals’ residential choices…) [6].

In France, a 2005 report [10] shows that there is no overexposure of ZUS, sensitive urban areas characterised by large areas of degraded housing and a marked imbalance between housing and employment to natural hazards. On the other hand, nearly 42% of municipalities with a ZUS are exposed to industrial risk compared to 21% for the others. This over-exposure of the ZUS is explained by the proximity between the workers’ districts and the factories, particularly in the “historical” industrial basins, but also by development choices, with affordable land).

Some researchers [11] have wanted to highlight the process of residential dynamics as the main explanatory reason for exposure disparities, considering that the individual choices (flight of the middle and upper categories of impacted areas; “choice” of households with low financial capacities to live where rents or properties are the cheapest) studied over time would deny any responsibility of developers and operators of infrastructure or plants. The latter would not make any decisions favouring inequalities, it is the individuals who would create this dynamic through their choice of place of residence. But this explanation severely limits the understanding of the phenomena leading to situations of environmental inequality and makes individual behaviour the basis of a much more complex socio-economic and territorial dynamic.

Environmental inequalities are not necessarily the sum of environmental issues and social inequalities: they arise from the encounter of an environmental problem and a population or territory that is particularly vulnerable in social, economic, cultural and/or political terms. The classification below illustrates this relationship.

3. Environmental inequalities: variety of configurations

The highlighting of these causal processes shows the diversity of the forms of environmental inequalities that result from social, territorial and historical constructions that must be analysed over a relatively long period of time in order to understand their production mechanisms and be able to overcome them. “Inequalities have their origin not in a natural order of things but in a certain historically determined institutional organization of social and ecological relations. “» [13]. Also a typology of possible cases based on the scientific literature and several fields of study allows us to appreciate the variety of possible configurations:

- differentiated exposure to an environmental impact (pollution, risks, etc.) of populations. In the United States, the awareness of cases of environmental injustice at the end of the 1970s was forged on concrete cases showing a “coincidence” between the location of highly polluting industrial infrastructures and the proximity of African-American and/or impoverished populations. [14]

- The shifting of impacts created by one another or in other words, the unequal contribution of people and populations to environmental problems. This can result, for example, in an ecologically unequal exchange between poor countries (supplier of raw resources and receiver of waste or polluting projects) and rich countries (principals and receivers of revenues from the processing and marketing of resource products) [15].

- differentiated access to “environmental” resources. It is necessary here to distinguish several configurations: (1) different access to resources necessary to meet basic needs (clean water, unpolluted soil, breathable air, etc.) and to fulfil vital functions (healthy food, heating, housing, etc.) [16] and (2) different distribution and accessibility of environmental amenities and ecosystem services among individuals and populations.

The second configuration is reflected in particular in the residential choices that are constrained and made by households according to a certain number of criteria (access to transport, proximity to public transport, etc.) and the means at their disposal to find accommodation and whether or not they meet the criteria mentioned above. Choice is therefore the subject of an even stronger trade-off for disadvantaged households as they will find it difficult to “choose” a pleasant and healthy environment, as long as it has an effect on prices. Indeed, a household with low social and economic resources has very limited margins of choice, faced with the imperative of having to find housing.

We can then highlight the differentiated access to environmental amenities [17], “i.e. the attributes, natural or shaped by man, linked to a space or territory and which differentiate it from other territories that do not have them” [18]. Getting to and enjoying green spaces, forests, riverbanks or coastlines requires a number of social, economic and cultural capital. Moving to this type of space involves costs and requires knowledge of the territory and its particular characteristics.

- the different capacity of the public to influence decisions affecting the environment, which results both from the capacity of the citizen to participate in decision-making processes (which varies according to the type of project, the willingness of planners and this, despite a persistent basis of participatory requirements included in many legislations), but also from the capital (social, cultural, economic, etc.) of populations and individuals enabling them to express themselves, make their voice heard and have their legitimacy as stakeholders recognised..

- the differentiated and potentially unequal effects of environmental policies [19] depending on the populations to whom they are addressed and imposed. A policy in favour of environmental preservation can have a negative impact in the fight against social inequalities. This is the case for traffic restriction schemes in metropolitan areas, which target older vehicles that are much more prevalent among low-income households. Even if they improve overall air quality and public health, if they are not accompanied by support and compensation measures, they can significantly reduce the mobility of disadvantaged populations [20] and shift pollution to peripheral and disadvantaged areas.

- justice with regard to the environment: the emergence of the theme of environmental justice has been in opposition to previous environmental movements. How can non-humans be taken into account in projects? How can we design the interface between nature, human activities and technical systems without irreversibly eroding biodiversity and natural balances, particularly climatic ones? The environmental justice movement and the conception of environmental inequalities have often from the outset overshadowed these issues [21]. Even today, the gap between social justice and ecological justice [22] still exists but is narrowing with the implementation of the most operational and sustainable mechanisms (such as social and natural based solutions).

These possible configurations cross most of the time and can be read at several scales. Thus, the unequal contribution to environmental damage can be seen at the global level through the effect of the globalization of flows. In 2006, a boat, the Probo Koala, spilled highly toxic substances in Abidjan, killing seventeen people and killing tens of thousands. The private company, an independent trader in petroleum products, which chartered it, could not get rid of this waste in Europe and therefore headed for Côte d’Ivoire in violation of European law which prohibits the export of certain types of waste from the EU to African, Caribbean and Pacific countries.

Similarly, this diversity makes it possible to highlight that environmental inequalities do not only reinforce social or spatial inequalities or lead to a re-reading of the latter through the prism of environmental issues. The latter can also structure spatial or social inequalities. Hence the modalities of remediation, repair or compensation depend on a detailed knowledge of the situation producing them.

4. Repair or compensation procedures

Over the past few decades, general principles aimed at improving human beings’ relationship to their immediate environment have emerged: the right to a healthy environment, the right to the city [24]… But how can they be made operational through concrete measures and regulations? Which conceptions of justice should apply: “egalitarian” vision “, utilitarianism, liberalism … ? But the complexity and diversity of these inequalities also imply a diversity of responses that are not always easy to design or implement. How do we proceed then?

- Removing the cause of negative impacts? It would therefore be necessary either to remove the infrastructure in question – which is difficult – or to avoid and reduce as much as possible these negative impacts, for example through the reduction of noise at source, the prohibition of toxic discharges, the landscaping of equipment..

- Treat the impact site through specific devices? Urban policy has used this principle by targeting specific resources in areas where poverty indicators were high; this has resulted in the financing of a series of actions in the fields of socio-professional integration, culture, etc., but also more structurally through the structuring of public and green spaces.

- Take specific actions towards vulnerable populations and strengthen their capacity for action and decision-making [25]? The environmental justice movement in the United States has sought to structure people living near polluting infrastructure, help them to make inequalities visible and then negotiate measures – where possible – to reduce the environmental burden.

- Let the actors (operator and local residents) develop local rebalancing solutions that compensate for irreducible negative effects and redistribute positive impacts? In the United States, for example, community benefits agreements [26] (CBA) are the result of an agreement between the developer and the population, as was the case for Los Angeles airport. This CBA includes a job exchange for residents affected by the impacts (and in particular Hispanic minorities), a program to reduce atmospheric emissions and sound insulation in public housing and facilities.

All existing measures are often inconsistent with each other and do not aim to reduce inequalities, despite the efforts of some communities. In the following sub-sections, we present mechanisms to shift costs to the one that produces the impact by modulating the polluter-pays principle, as well as how the issue appears on the political agenda (local and national) in the United States and France.

4.1. Forms of internalisation: from legislation to negotiation

- specific legislation requiring the developer/operator to take the necessary measures to reduce the effect and/or impact on populations and environments,

- taxation arrangements (e.g. in France, the General Tax on Polluting Activities [1]) which then provide the necessary revenue for the implementation of measures to reduce or compensate for impacts (soundproofing of housing and public buildings located near airports through the TNSA, noise pollution tax); (Figure 7).

- the negotiation of socio-environmental compensation or compensation, which often arises as a result of a conflict between the developer/operator and the riparian pole, which can lead to a reversal of power relations between riparians and developers. Since socio-environmental compensation may be the result of local negotiations, there is no guarantee that appropriate solutions will be found in another territory in a similar configuration. This “situated justice”, however effective it may be at a specific scale, raises the question of its reproduction on other spaces and at other scales, in contrast to the previous systems mentioned above.

4.2. A political issue that is more or less integrated into the political agenda

In the early 1990s, the activism of associations and opinion leaders made it possible to institutionalize environmental justice. Thus is taken by President Bill Clinton, Executive Order 12898 requiring all federal agencies to integrate an objective of environmental justice by identifying and addressing any impact that would disproportionately affect the poor or minority populations, or jeopardize their health. Specific structures were created: the Environmental Justice Office and the National Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (NEJAC). Moreover, twenty years later, the results of this integration into the political agenda remain relatively meagre in order to reduce the burden of nuisances, risks and pollution on minorities and poor populations and are more readable from a procedural point of view. Indeed, even if there is an obligation to take into account in the paper-based procedures of environmental justice communities, the reality remains the same in terms of overexposure of minority populations.

In France [28], environmental inequalities are currently mainly addressed through three main channels: environmental health through the National Environmental Health Plan, fuel poverty [29] and access to healthy food. Environmental inequalities are increasingly tending to integrate the public agenda and question the practices of planners. As announced by N. Hulot, “in this[energy] transition, it will be necessary to take into account the social dimension” “but the practical details remain unclear [30].

Environmental inequalities are not a new phenomenon; situations of social vulnerability coupled with environmental situations (exposure to pollutants, lack of access to amenities, etc.) and problematic territorial discrimination have a long history. But a new perspective has been brought to the latter, on the one hand with the emergence of environmental concerns [31] and their institutionalization at the end of the 1960s; on the other hand because of citizen and scientific mobilization, denouncing and studying the overexposure suffered by certain populations.

These inequalities are not natural, resulting from a geographical determinism; they have historically, socially and culturally emerged through the way land is developed, certain populations are treated, natural resources are exploited, economic activities are distributed… In this respect, they constitute a large area of political appropriation to be avoided, reduced or compensated.

Thus, their understanding and remediation require them not to think about environmental problems from a technical point of view alone, but to rethink territories and their development, as well as environmental policies, in order not to overlook their social impacts. The environmental issue cannot be dehumanized and desocialized, precisely because human beings and their activities are at the root of the scarcity of resources, their pollution and, in part, the unequal distribution of a number of environmental ills and goods.

References and notes

Cover image. Dharavi slum in Mumbai district (Bombay, India), near Mahim Junction. The inhabitants of these slums suffer, without being able to do anything about it, from the various risks and pollution associated with their environment. [Source: By A. Savin (Wikimedia Commons – WikiPhotoSpace) (Own work)[FAL], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1]Larrère, C. (2017) Les inégalités environnementales, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, p. 12

[2] WHO (2016), Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease,[Online] : http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250141/1/9789241511353-eng.pdf?ua=1

[3] NIJKAMP P. et al., (1992), “Sustainable Development in a Regional System”, in: M. J. Breheny (ed.), Sustainable Development and Urban Form, Series editor P.W. J. Batey, pp. 39-66.

[4] Faburel G. (coord.) (2006) Les effets des trafics aériens autour des aéroports franciliens. Volume 1: State of knowledge and assessment methods on environmental themes, CRETEIL Report for UNA-Canada, ADP and DGAC, May, 158 p.

[5] That is, how to plan the city, how to structure development operations, such as urban renewal, infrastructure installation or equipment construction

[6] MASSEY D., DENTON N. (1993) American Apartheid, Havard University Press

[7] “All interventions (on housing supply, on allocations or on social support) carried out by actors (institutional and operational) in order to modify the occupation of social housing” (ANRU Monitoring Committee, 2014)

[8] Sala Pala, V., Kullberg, J., Tomlins, R. and Henry, G. (2005) Housing policies and ethnic minorities in the European Union, in Les minorités ethniques dans l’Union européenne, La Découverte.

[9] Clerval A., Fleury A. (2009) “Urban policies and gentrification, a critical analysis based on the Paris case”, L’Espace Politique[On line], 8 : https://espacepolitique.revues.org/1314

[10] Report of the General Inspectorate of the Environment on ecological inequalities in urban areas of 2005 Report available online: http://cgedd.documentation.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/documents/cgedd/2004-0116-01.pdf

[11] BEEN, V., GUPTA, F. (1997) Coming to the Nuisance or Going to the Barrios? A Longitudinal Analysis of Environmental Justice Claims, Ecology Law Quaterly, n°24-1, p 1-56

[12] Bone, R., Anderson, R. (2017), Indigenous Peoples and Resource Development in Canada, 506 p. Captus Press.

[13] Centemeri L., Renou G., 2017, “How far does the ecological economy think about environmental inequality? Around the work of Joan Martinez Alier”, in Larrère, C. (2017), p 53-72

[14] TAYLOR, D.E. (2014). Toxic Communities. Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution and residential Mobility. New York: New York University Press.

[15] Martinez-Alier, J. (2014). L’écologisme des pauvres, Une étude des conflits environnementaux dans le monde, Paris: Les Petits Matins.

[16] Harpet, C., Billet, P. (2016), Justice and environmental injustices, L’Harmattan.

[17] Kalaora, B. (1998) Au-delà de la nature l’environnement, L’observation sociale de l’environnement, Paris: L’Harmattan; Deldrève, V. (2011). Preservation of the coastal environment and ecological inequalities: The example of Le Touquet-Paris-Plage. Spaces and societies, 144-145.

[18] OECD (1999), Biodiversity Protection Manual: Design and Implementation of Incentives, Paris.

[19] Deldrève, V., Candau, J. (2014) Producing fair environmental inequalities? Sociology, 3 Vol. 5, p. 255-269.

[20] La Branche, S., Charles, L. (2012) Étude d’acceptabilité sociale de la ZAPA de l’agglomération grenobloise: synthèse des principaux résultats. Air Pollution: Climate, Health, Society, Air Pollution, p.226-230; Gobert, J. (2015) Socio-environmental compensatory measures and social acceptance, in Levrel H. et al., Restoring nature to mitigate development impacts- Analysis of compensatory measures for biodiversity, QUAE, p. 34-44.

[21] SZE, J., London, J., (2009) Environmental Justice at the Crossroads, Sociology Compass, No. 2, vol. 4, pp. 1331-1354.

[22] Shoreman-Ouimet E., Kopnina H., 2015, Reconciling ecological and social justice to promote biodiversity conservation, Biological conservation, 184, pp. 320-326.

[23] Kelly-Reif, K., Wing, S. (2016) Urban-rural exploitation: An underappreciated dimension of environmental injustice, Journal of Rural Studies, Vol. 47 A, pp. 350-358.

[24] LEFEBVRE H. (1968) Le droit à la ville, Paris: Anthropos.

[25] Sen, A. (1985) Commodities and Capabilities, Oxford: Elsevier Science Publishers.

[26] Videos on CBAs: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=163&v=dlUn_tdloYE / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zn_LBu3drE

[27] TGAP is due by companies whose activity or products are considered as pollutants: waste, polluting emissions, lubricating oils and preparations, detergents, extraction materials, etc.

[28] The question of the effects of a polluted environment on vulnerable populations does not date back to the recent acclimatization of “environmental justice” in France. The major epidemiological studies of the 19th century highlight the living conditions of workers in a particular environment.

[29] That is, the difficulty of poor households to pay energy bills, and therefore on the one hand to be able to live in decent conditions with very ambitious national renovation objectives within the framework of the Energy Transition Law.

[30] Nicolas Hulot, Minister of State for the Environment, 2017.

[31] Here again, there is no particular recency. Historians show that as early as the 19th century, the increasing scarcity of resources and biodiversity began to question scientists. LUGLIA, R (2015), Scientists to protect nature. The acclimatization society (1854-1960). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: GOBERT Julie (February 7, 2019), Environmental inequalities, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed March 30, 2025 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/environmental-inequalities/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.