Reproductive strategies of alpine plants

PDF

When environmental conditions are difficult or peculiar, such as in high mountains, plants must adapt to ensure their reproduction. Two main strategies allow alpine plants to persist generation after generation: the maintenance of sexual reproduction or the use of vegetative reproduction. This diversity will be highlighted through several examples of alpine plants that have adapted to their environment.

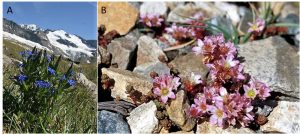

“Alpine” environments are environments which are found above the natural limit of the forest, in the absence of human intervention, in any part of the world: Alps, Andes Cordillera, Himalayas, New Zealand… These cold environments are often characterized by a very short growing season, with few sites suitable for seed establishment, difficult pollination due to the rarity of insects and violent winds as well as high interannual variability of climatic conditions.

Two main strategies allow alpine plants to persist, generation after generation: maintaining sexual reproduction or the use of vegetative reproduction.

1. Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a source of genetic diversity that allows animal and plant populations to cope with fluctuations in their environment. In plants, it involves the production of flowers, their pollination, the maturation of seeds and their dissemination and germination, all of which are often hazardous stages in alpine areas. Several strategies can be used to overcome environmental constraints.

1.1. Long life

The Alpine flora has less than 2% of annual alpine plants [1] (Figure 1) which depend exclusively on the success of sexual reproduction and therefore on the environment. Even if seeds are produced on time, they require new sites for germination, often limited due to the presence of bedrock (rocky areas, screes) and the presence of other species. On the contrary, perennial species can wait for favourable conditions to reproduce (Figure 2). In contrast, in arid and Mediterranean alpine biotopes, annual plants are more widespread [2]. The seeds then represent a form of resistance.

1.2. Spread reproduction over several years

1.3. Increase flowering time

1.4. Playing with colour?

Flowers are said to be more colourful at higher elevations to attract pollinators more effectively (Figure 5). In fact, there is no significant increase in colour, size or other characteristics associated with insect attraction [3]. The mountains of New Zealand are a remarkable example: the vast majority of species have white flowers (Figure 6).

2. Conquering the territory: vegetative reproduction

To avoid the hazards of sexual reproduction, many alpine plants use vegetative reproduction. This is not a specificity of mountain plants; however, the proportion of alpine plants using this reproductive strategy increases with altitude [1]. All vegetative reproduction modes are present in alpine plants: production of rhizomes or stolons, formation of dense tufts, stuckers, reproduction by layering but also viviparity and apomixis.

2.1. Rhizomes and stolons

2.2. Stuckers, tufts and layering

In the case of layering, rooting occurs when branches come in contact with the soil as shown in Figure 9 in the thyme-leaved willow. Short bushes of alpine rose (rhododendron moors) or willows can shelter several genets (genetic individuals), each made up of dozens of ramets, all forming a somewhat impenetrable canopy. Only a genetic analysis can allow to distinguish the different genets.

2.3. Viviparity

Viviparity, for example through the production of bulbils that begin to develop on the mother plant, and apomixis ensure dispersion over greater distances. Figure 10 shows the inflorescence of the alpine bistort (Polygonum viviparum L., Polygonaceae), illustrating the combination on the same floral stem of sexually reproducing flowers and bulbils produced by asexual reproduction. Since the stem length available for flowers and bulbils is constant, the proportion of bulbils increases with altitude and latitude. In other words, clonal reproduction is more important when living conditions become more difficult [1].

3. How do plants deal with environmental change?

With their multiple modes of reproduction, alpine plants are adapted to their environment. These modes of reproduction are very effective both for the stability of the environment and for the maintenance of genetic diversity. This genetic diversity may be an opportunity for the alpine flora, which is currently facing major climate change, with a temperature increase expected during this century ranging from 2 to 8°C. This warming, which is very rapid compared to temperature fluctuations during the alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods, will lead to an upslope displacement of vegetation belts and will reduce the sites favourable to alpine flora.

References and notes

Cover image. The Meige massif seen from the Lautaret Alpine Garden [Source: © Photo Joseph Fourier Alpine Station/Serge Aubert]

[1] Körner C (1999) Alpine plant life, Functional plant ecology of high mountain ecosystems. Springer-Verlag Publishing

[2] Arroyo MTK et al (1998) The flora of Llullaillaco National Park located in the transitional winter-summer rainfall area of the northern Chilean Andes. Gayana Botanica 55:93-110

[3] Totland Ø et al (2005) Abstract No. 13.10.2. 17th International Botanical Congress, Vienna

[4] Steinger T, Körner C & Schmid B (1996) Long-term persistence in a changing climate: DNA analysis suggests very old ages of clones of alpine Carex curvula. Oecologia 105:307-324

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: TILL-BOTTRAUD Irène, AUBERT† Serge, DOUZET Rolland (January 5, 2025), Reproductive strategies of alpine plants, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed April 2, 2025 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/life/reproductive-strategies-of-alpine-plants-2/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.