Earth’s atmosphere and gaseous envelope

PDF

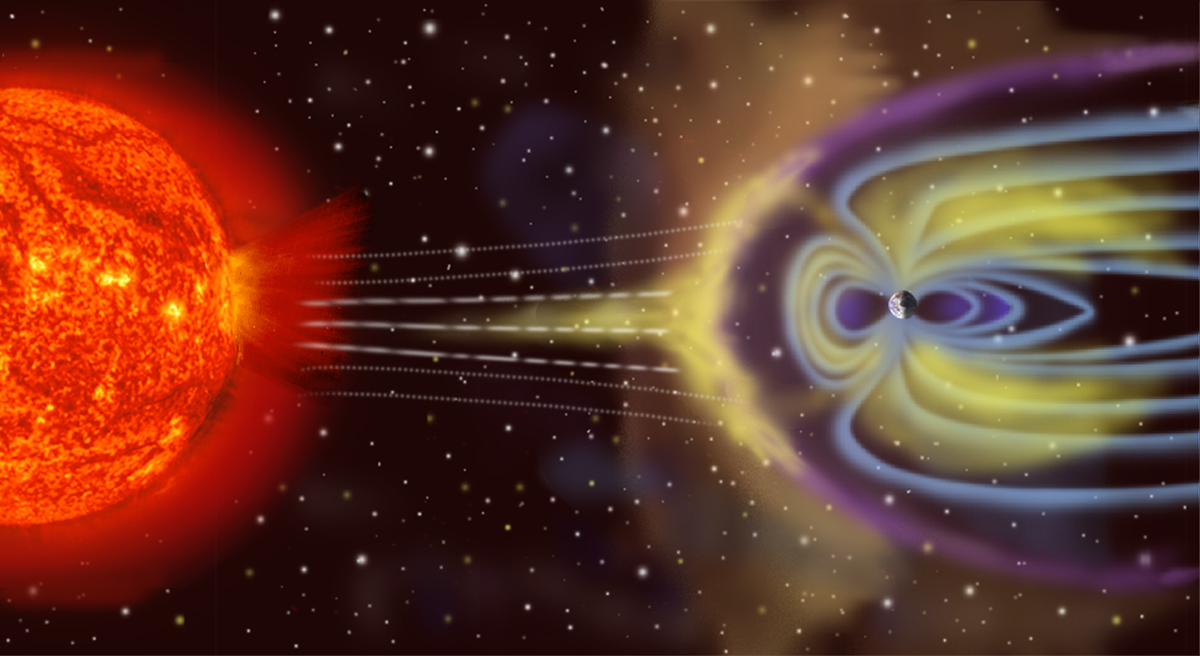

The Earth is surrounded by a gaseous domain, commonly referred to as the atmosphere, although, etymologically, this name is only justified for the lowest and densest layer, where the oxygen content allows humans to breathe. In this gaseous envelope, use leads to the distinction of several concentric layers, the troposphere up to about 12 km, then the stratosphere up to about 60 km and finally the mesosphere, up to altitudes beyond which the air becomes too rarefied to be modelled as a gas. The mechanisms specific to each of these layers justify their names; they impose a non-monotonous temperature variation, while pressure and density decrease regularly with altitude. This gaseous layer has a crucial influence on living conditions on Earth, both through its action on the climate, notably through the greenhouse effect, and through its role as a shield that filters a large part of the Sun’s radiation.

1. The layered structure of the atmosphere

The main characteristic of this medium is its gaseous nature, which means that molecules, which are constantly agitated at speeds above the speed of sound (about 340 m/s in air at sea level), have extremely frequent collisions. Let us be more precise: in air at moderate altitudes, the typical time between two collisions (about 10-9 seconds at sea level) is much shorter than the travel times of birds and aircraft flying in this environment, or than the characteristic wind and atmospheric flows. Beyond that, in the Earth’s space environment (see The Upper Atmosphere), the distances between molecules, atoms or ions are so large that this condition is no longer fulfilled and that this environment cannot be modelled as a gas. Moreover, this gaseous envelope is almost transparent to electromagnetic waves and therefore to light, but leaves acoustic waves (sounds) only a relatively limited range due to the viscosity of the air, sufficient to dissipate their energy.

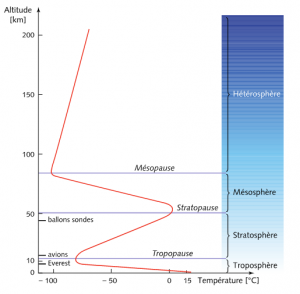

Three of the most significant phenomena, heat transfer by conduction and convection [1], water content and absorption of ultraviolet radiation emitted by the Sun are used to define the concentric layers that make up the atmosphere. Between the ground and an altitude of around 8 km at the poles and 15 km at the equator, heat transfer by conduction and convection prevails and imposes a linear decrease in temperature: on average 6.5°C/km, a quantity that can vary between 5°C /km in air saturated with water vapour and 9°C/km in dry air (Figure 2). Why does the water vapour content influence this temperature distribution so much? This is due to the phenomenon of condensation that occurs at higher and higher altitudes, when the temperature and pressure decrease and the agitation of the nitrogen and oxygen molecules is no longer sufficient to carry the water molecules. This condensation releases latent heat (see Pressure, temperature and heat) which reduces the linear cooling of the temperature. This first layer is called the troposphere. It is the densest, wettest and most agitated. Its agitation comes from natural convection due to the fact that the hottest, and therefore lightest, gas is often located below a heavier gas, and from winds that are more or less organized on a global scale (see Atmospheric circulation: its organization).

Beyond the tropopause, the upper limit of the troposphere, the gas is too rarefied to efficiently transport heat by conduction and convection; it is then the absorption of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun that becomes predominant. It causes chemical reactions that transform oxygen (O2) into ozone (O3). These are exothermic (in other words, they release heat) and thus warm up a second layer, called the stratosphere, because it is possible to distinguish several sub-layers, or strata, depending on their oxygen and ozone composition. These strata are visible on Figure 1. The temperature is around -56°C in the tropopause, then rises to values close to 0°C in the stratopause, the upper limit of the stratosphere. Unlike the troposphere, in this stratified layer, the heaviest gas is systematically located below a lighter gas, which gives it very high stability and prevents the agitation of the troposphere from disturbing it. And even further from the ground, a third layer, the mesosphere, is so diluted that the absorption of ultraviolet rays is much less significant, which again causes a decrease in temperature with altitude. Figure 2 illustrates these three layers, their separations, and the transition to the heterosphere (see Upper Atmosphere), beyond the mesopause, the upper limit of the mesosphere.

2. How the properties of the atmosphere vary with altitude

– An exponentially decreasing pressure

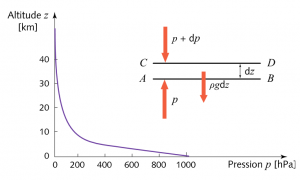

Since this gaseous medium moves very slowly with respect to the proper movement of its molecules, it is justified to consider it as a fluid at rest and in equilibrium under the action of gravity. This equilibrium state is characterized by several variables that depend on altitude. The pressure within this gas is not subjected to any force other than gravity and this implies the exponential decrease illustrated in Figure 3, the justification for which can be found in Air and Water [2]. This exponential law requires that the pressure decrease as a function of altitude be proportional to the local pressure, high at sea level, where the pressure is maximum (1013 hPa) and lower and lower as altitude increases (the Pascal is the pressure unit of the international system: 1 Pa=1 N/m2 or newton per square meter).

– A homogeneous composition

But the air in the troposphere is not dry, except at very great distances from water bodies that are sources of evaporation. Its water vapor content varies from zero in dry weather to its maximum possible, known as the saturation vapour pressure. Beyond this maximum, the water condenses into droplets, which form fogs and clouds. This saturation vapour pressure depends both on temperature (the partial pressure of water vapour increases from 0.6% of atmospheric pressure at 0°C to 7.4% at 40°C) and on local pressure: clouds form in depressions that bring rain and disappear in anticyclones where the pressure is higher than its average value.

– Where pressure decreases, oxygen is running out

The fact that the pressure undergoes a continuous and exponential decrease to its near zero limit beyond 40 km has important consequences for all forms of life (see The Origin of Life as seen by a geologist who loves astronomy). In the troposphere, where the absolute temperature [3] varies moderately (from 288 K on the ground to 200 K in the tropopause, where K is the kelvin, the temperature unit of the international system), the oxygen content varies almost like the pressure. At the top of Mont Blanc (4810 m), it has been halved. This means that before any hiking or climbing effort a mountaineer must breathe twice as fast as at sea level to provide the same amount of oxygen to his body, increasing his heart rate from 60 beats per minute to 120. This exercise is accessible to many healthy people and explains the large number of people attending this emblematic summit. In contrast, the high peaks of the Himalayas reach around 8000 m, where pressure and oxygen content have been reduced by a factor of three. Having to breathe three times faster than at sea level, before any effort is made, the hiker must raise his heart rate to 180 beats per minute, which makes hiking efforts almost impossible. This is why these high peaks are reserved for specially trained athletes who have been able to reduce heir normal heart rate to 50 beats per minute or less.

– As the density decreases, it becomes more difficult to fly

The mass per unit volume of air within the homosphere, often referred to as its density, is related to pressure and temperature by the equation of state of this gas, which is diluted enough to be assimilated to a perfect gas (see Pressure, temperature and heat). Since the absolute temperature varies relatively little, while the pressure varies from its maximum at sea level to almost zero values in the mesosphere, it is classic to consider that the density also varies exponentially. This rapid decrease in air density explains why birds only fly in the lower layers of the troposphere where they find air dense enough to carry them. Similarly, airliners, whose weight must be compensated, can only fly in the troposphere, where their large wingspan receives sufficient lift. Rockets, which go into the stratosphere and beyond, no longer have wings but only a small tail to stabilize them.

3. Heat transfer in the atmosphere

It was mentioned above that the temperature distribution within the troposphere decreases linearly from an average sea level value of about 15°C (see Figure 2). The key to understand this linear temperature distribution within the troposphere is the analysis of heat exchanges between the Sun, the Earth and its atmosphere. This question forms the basis for any analysis of climate variations, which is the subject of another section of this encyclopedia, of which this paragraph is only a brief introduction. The articles Radiation and Climate (link) and The Climate Machine in this encyclopedia provide a more precise and better documented analysis. The heat flux radiated by the Sun towards the Earth is about 1361 W/m2 (the watt is the power unit of the international system: 1W=1Joule/s=1N.m/s) at the average Earth-Sun distance; it varies during the year because of eccentricity (about 5%). This magnitude varies very slowly, essentially in accordance with the rhythm of variations in the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, over periods of about 100,000 years. Its variation is one of the causes of the alternation of glaciations and interglacial remissions such as the one we are experiencing, called the Holocene.

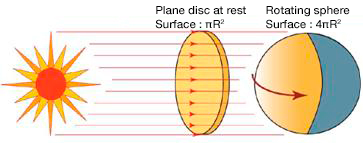

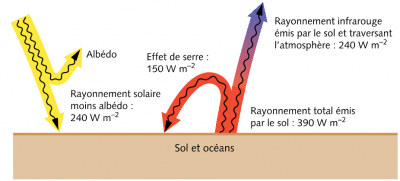

Two corrections are essential to deduce the heating of the Earth [4], [5]. First, we must subtract the albedo, that is, the fraction of this energy reflected back into space mainly from clouds, snow-covered surfaces and oceans. This reduces the heat flow to about 950 W/m2. Moreover, since the Earth is not an area disc πR2 but an area sphere 4πR2, this value must be further divided by four (Figure 4). This results in an average flow of 240 W/m2. And for the average ground temperature to vary only slightly, there must be a thermal balance such that it radiates the same 240 W/m2 flux towards space.

4. Messages to remember

- The Earth’s atmosphere is structured in 3 gaseous layers: the troposphere, dense enough to allow life and flight for birds and airplanes, the stratosphere, which protects us from the ultraviolet radiation emitted by the Sun, and the distant mesosphere, which is extremely sparse.

- The air in the atmosphere is made up of 4 major gases whose proportions do not vary much with altitude: nitrogen (71%),oxygen (21%), argon (1%) and carbon dioxide (0.035%).

- Heat exchange within the atmosphere determines the Earth’s average temperature. The average heat flux radiated by the Sun that reaches the ground is about 240 W/m2 and the average temperature of the planet must be such that its own radiation to space has exactly the same value. As a result, this average temperature is close to +15°C (or 288 K).

- These radiated fluxes are influenced by two important effects: the albedo, which reduces the solar radiation reaching the ground and redirects it towards space, and the greenhouse effect, which intercepts part of the Earth’s infrared radiation towards space and returns it to the ground.

References and notes

[1] Conduction is the mode of heat transfer within a material at rest in the absence of radiation; it results from the agitation of elementary particles, the molecules in the case of gases. Convection refers to the complementary contribution due to movement, which amplifies this heat transfer by evacuating the hot fluid and replacing it with cold fluid, which in turn heats up and so on.

[2] Air and water, René Moreau, EDP sciences, Grenoble sciences collection, 2013

[3] The absolute temperature is counted from absolute zero. It is equal to the temperature in degrees centigrade, counted from a conventional origin, that of melting ice at sea level, increased by 273.15. It is measured in kelvin (K).

[4] Is Man responsible for global warming? André Legendre, EDP Sciences, 2009

[5] Humanity in the face of climate change, Robert Dautray and Jacques Lesourne, Odile Jacob sciences, 2009

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: MOREAU René (January 5, 2025), Earth’s atmosphere and gaseous envelope, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed March 31, 2025 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/air-en/earths-atmosphere-and-gaseous-envelope/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.