绿色长城:绿化萨赫勒的希望?

“非洲绿色长城”(GGW)是一项旨在防治撒哈拉沙漠和萨赫勒地区荒漠化的泛非倡议。GGW的最初构想是一个从西到东横穿非洲大陆的大规模植树造林行动,现已发展成为一系列改善环境和人类福祉的修复项目。鉴于既定的环境和社会目标,所有学科的研究人员都在汇集专业知识、指导管理项目机构决策中发挥重要的作用。虽然GGW不再是政治行动者最初设想的简单的“树木长城”,但植物和植被重建仍然是该项目的核心,因为萨赫勒地区的人民比其他任何地方都更加依赖植物资源来满足日常需要。在经历社会和生态转型的萨赫勒地区,真正的挑战是在保护和可持续利用植物资源之间找到平衡。

1. 绿色长城:非洲应对全球社会环境挑战的对策

萨赫勒地区被认为是地球上最脆弱的地区之一。这是由草原、稀树草原和乔木组成的生态系统,从西到东横穿非洲大陆,标志着从非洲北部撒哈拉沙漠到非洲南部苏丹地区之间的生态地理过渡。由于该地区的人为压力和水文气候不稳定,这些主要服务于畜牧业的生态系统非常脆弱。

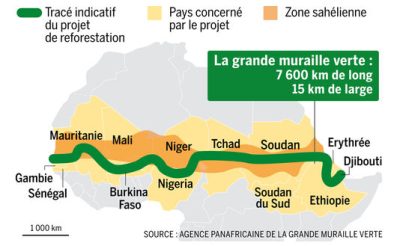

(图1 Zone sahélienne 萨赫勒地区;Tracé indicatif du projet de reforestation 植树造林项目;Pays concerné par le projet 项目所涉及的国家;La grande muraille verte : 绿色长城;7 600 km de long 15 km de large:长7600公里,宽15公里;Gambie 冈比亚;Sénégal 塞内加尔;Mauritanie 毛里塔尼亚;Mali 马里;Niger 尼日尔;Tchad 乍得;Soudan 苏丹;Burkina Faso 布基纳法索;Nigeria 尼日利亚;Soudan du Sud 南苏丹;Ethiopie 埃塞俄比亚;Erythrée 厄立特里亚;Djibouti 吉布提;SOURCE : AGENCE PANAFRICAINE DE LA GRANDE MURAILLE VERTE 资料来源:绿色长城泛非机构)

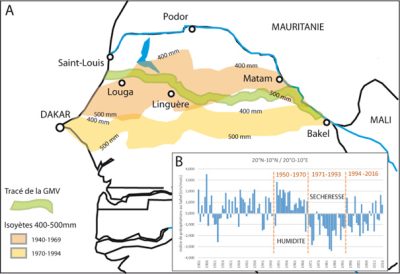

GGW是在高度受限环境下开展起来防治荒漠化的手段(图1)。它覆盖了年降雨量100至400毫米的地带。萨赫勒地区被确定为世界气候变化的“热点”之一[1],到2100年气温预计将上升3-6℃[2],预期后果尤其令人担忧。年降雨量低是植树造林恢复生物多样性的主要障碍。该地区降雨主要集中于7月到9月,以偶发强降雨形式出现。降雨年际变化大,易导致干旱:1970年至1993年期间,该地区经历了几次后果严重的危机[3]。例如,在塞内加尔,与1940-1969年相比,1970-1994年年降水量为400-500毫米的地区向南移动约200公里,导致“绿色长城”所在纬度的降水量急剧减少(图2A)。此外,如萨赫勒地区的降雨指数所示(图2B),三十年的湿润期之后出现了二十三年的异常干旱期(1971-1993年)。自1994年以来,萨赫勒西部的降雨情况再次好转,但与20世纪上半叶的情况不同。气候变化可能导致更极端的气候,如更严重的干旱和更强烈但频率更低的降水[4]。

自1970年代以来,国际发展机构定期在萨赫勒发生危机时进行干预。由于此类工作趋向于应对短期和紧急情况下的挑战,针对表面问题而不是根本原因,他们采取的行动往往以失败告终。为应对这些一再发生的社会生态危机,2007年,一项雄心勃勃的泛非方案启动——“撒哈拉和萨赫勒绿色长城倡议”(GGW),即建立一条横跨非洲大陆长7000多公里、宽15公里的植树造林带。该倡议得到了11个创始国的国家元首采纳(图1)。这一倡议的最初目标是对抗荒漠化的有害影响,阻止沙漠扩张。由于以下原因,萨赫勒地区的一些专家和科学界对GGW表示质疑:

- 对荒漠化的原因了解不足;

- 大规模的造林行动被认为不可行,且具有不良影响,等等……

自启动以来,GGW已朝着更现实的愿景发展,以更合理的方式应对区域挑战。它现在采取综合景观管理的方法开展一系列恢复行动,这些行动在地理上相互关联,目的是改善萨赫勒地区环境和人民的社会经济福祉。

自启动以来,GGW已高度多样化,包括建立围栏地块供树木自然再生以及防止过度放牧,建立由妇女管理的社区花园,设立动物保护区项目,发展养蜂业……然而,“合理的重新造林”和植物资源管理仍然是萨赫勒地区绿化和保护环境的重要手段之一。大规模植树造林是当前全球性问题应对的一部分。例如,“波恩挑战”的目标是到2030年恢复35亿公顷被砍伐的森林土地。作为全球森林管理的一项行动,重新造林也符合联合国成员国制定的可持续发展目标中的第15项,“保护、恢复和促进可持续利用陆地生态系统,可持续管理森林,防治荒漠化,制止和扭转土地退化,遏制生物多样性的丧失”[5]。

为了实现其目标,GGW必须广泛利用各科学领域知识,将其融入决策过程。例如,萨赫勒地区景观的明显同质性可能导致干预措施简单化和定型化(解决方案数量减少)。然而,萨赫勒地区实际上是由空间上相互交织的多种社会生态系统组成的。为了管理自然资源,不仅要考虑生态系统的生物物理组分,还要考虑人类组分,以及两者之间存在的复杂的相互作用。正是这些相互作用决定了社会生态系统的特性。了解社会生态系统及其功能需要跨学科研究,研究人员将研究成果传递给管理人员,为GGW建设发挥更全面成熟的作用[6]。虽然GGW的行动随着时间的推移已经变得多样化,植被研究仍然是解决方案的核心,高质量再造林的标准之一是其生物多样性程度。

2. 使GGW沿线的生物多样性最大化

生物多样性丧失是一个重大的全球问题[7]。GGW在扭转整个非洲大陆生物多样性流失方面可以发挥作用。在地方层面,萨赫勒人口高度依赖木本植物的生物多样性为其提供生态系统服务,满足食物、健康、薪材、建筑木材等方面的日常需求。然而,在萨赫勒的大部分地区,木本物种的生物多样性正在下降:从数量上看,建立在六钻林牧保护区(塞内加尔北部)以监测GGW的社会环境影响的CNRS人类环境观测站只记录了属于13个科的20个物种[8]。

GGW提出一个由100%的本土物种组成的重新造林(图3)计划。物种的选择除了上述第一个标准外,还要考虑当地人对这些物种的传统利用以及物种的生态适应性。为此,研究人员对当地人口进行了民族植物学研究,确定了树种(图4)。除了建立树种清单外,这项研究还可以确定树木的用途以及人们与树种的日常关系。针对最具价值树种的再造林可行性在两个试验区内进行了原位研究。来自GGW苗圃的13种萨赫勒植物物种被栽种,在之后若干年监测幼树的存活率、生长状况和生物量生产。这种方法将民族植物学和实验相结合,在此基础上向负责GGW的部门提出建议[9]:

- 重新造林增加的生物多样性不会超过木本植物自然再生(即在一定时间内将动物和人类排除在外,让自然得到休息)达到的生物多样性;

- 尽管GGW沿线的生态地理条件具有显著相似性,但支持物种生长的条件并不一致。

虽然在条件最恶劣的地点很少有物种能顽强生存,但在其他地点,可能成功的木本物种数量要多得多,这将增加生物量和生物多样性。这项研究还提供了提高物种存活率的技术信息(植物移栽时的年龄、种子来源、移栽条件,例如通过覆盖和添加有机物保护幼苗)。这些实验地点构成了露天实验室,可以在其中监测生态系统的其他组成部分(植物、动物、昆虫等)和气候参数,以衡量重新造林对“改良生态系统”的总体影响。

3. 更好地评估最具适应能力的木本物种

在GGW沿线上增加物种多样性很重要,但更好地利用在该地区自然繁衍的物种也很重要。在列出的20种常见木本植物中,有4种属于金合欢属(Acacia)植物。金合欢属(Acacia)植物的环境附加值在于通过根系中的特殊共生根瘤固定大气中的氮。这种固氮作用有助于恢复萨赫勒极贫瘠土壤的肥力(参见《靠空气生存的植物》)。金合欢(Acacia)的种植常见于农林复合经营,这是一种将耕种植物与树木植被相结合的互利农业经营方式。其中,塞内加尔金合欢树(Acacia senegal)因其阿拉伯树胶的产量和质量,有着很好的经济前景(图5)。

在被考虑的物种中,有一个树种几乎在GGW所有沿线国家被一致用作再造林物种——埃及槲果(Balanites aegyptiaca),即“沙漠椰枣”。该物种在干旱地区具有无与伦比的生命力,因此在塞内加尔萨赫勒地区的景观中占主导地位,占某些地区木本种群的50%[10]。该树种旺盛的生命力归功于其即使在最恶劣的条件下也能维系的生殖和营养繁殖能力。从形态学上看,“沙漠椰枣”的叶子表面积很小,表皮硬,有一层厚厚的蜡状表皮层,叶绿素的部位呈刺状,所有这些都是为了避免水分流失(图6)。

“沙漠椰枣”的根系同样壮观。将幼苗移栽后即使马上遇到旱季,其发育也非常迅速,而地上部分发育要慢得多。“沙漠椰枣”的根系形态具有双重系统,结构效率高:侧根生长在土壤表面附近,即使是稀薄的降水也能吸收;而主根生长得很深,可以汲取深层水资源[11]。

埃及槲果不仅健壮,根据民族植物学研究,它也被当地人评为最有用的木本物种。当地人主要将其用作食品、药品、薪材和建筑[12]。该植物对人类的重要性并不是近期才发现:其用途可以追溯到大约4000年前的埃及第十二王朝时期 [13]。今天,如果此树的所有部分都得到充分认识和利用,那么最重要的是其果实中蕴含的社会经济潜力。与其他热带水果相比,其果肉具有很高的营养价值:富含钾、钙、镁、铁和锌[14];果仁含有高达50%的优质油脂,富含不饱和脂肪酸(亚油酸和油酸)。提取的油可食用,也可以用于某些化妆品,但没有摩洛哥坚果油和乳木果油的利用普遍[15]。埃及槲果的销售受到当地非正式贸易的制约,远未发挥其经济潜力。

虽然研究让人们更好地了解了决定该物种经济价值的环境和遗传因素(果实大小和营养价值、果仁的含油量),但要使埃及槲果(Balanites)为萨赫勒地区人口带来显著经济收入还需要更大的努力。

4. 科学为绿色长城服务

萨赫勒地区几乎不可能变成伊甸园,但是该地区确实在渐渐恢复绿色[16]。科学家用可靠的科学数据进行评估,就可采取的行动进行充分讨论,支持了GGW行动,推动了该地区重现绿色[17]。

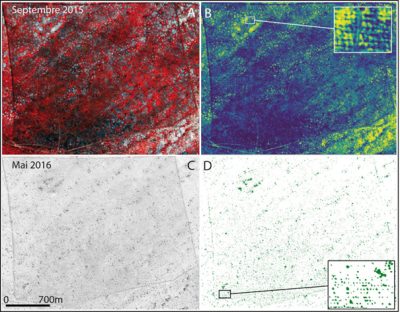

在物种层面上,我们能够在古老且经过验证的传统实践与现代科学(选择更能适应干旱的新品种,预接种植物菌根真菌[19],利用可以改善植物矿物质营养和水分的有益土壤微生物)之间找到正确的平衡(zai、demi-lune[18])。在景观层面上,可以利用超高分辨率的卫星数据:

- 使用空间分析技术定量评估GGW再造林(成功率与土壤持水能力的关系,GGW的固碳价值),

- 前瞻性地利用这些结果来确定和选择未来重新造林行动成功率高的区域(图7)。

最后,为了降低萨赫勒地区人口对反复发生的危机的脆弱性,科学家们正在研究社会生态恢复力,并试图找出增强恢复力的方法。通过集体工作,研究人员和利益相关者(治理参与者、环境管理者、当地居民和研究人员)分享了他们的知识和观点。他们一起研究自然资源管理、社会动态、实践和当地生产系统。该方法的最终目标是共同确定一套公平和可持续发展的目标,将改善人民生活条件与保护环境结合起来。他们的工作考虑到社会生态系统的复杂性、当地居民的愿望、社会和环境制约因素,并提出了最适当的自然资源管理办法。这些集体活动产生的具体行动需要赋予社会生态系统更大的恢复力,即提高其抵御未来灾害的能力,积极(甚至主动)适应负面影响,从而实现可持续繁荣发展。目前,新一代“恢复力评估”协议正在落实。这些协议共享相同的原则:一方面是跨学科原则,因为必须考虑所有社会和环境动态;另一方面是相关行动者的积极参与,因为他们的知识和期望是推动未来相关发展的必要条件(图8)[20]。

5. 总结

- 萨赫勒地区受到严重的水文气候和人为因素的制约,生态环境非常脆弱(土壤侵蚀、荒漠化、生物多样性丧失、营养不良)。

- 在前所未有的人口增长和持续的气候变化的负面影响下,其脆弱性在未来必然会增加。

- 只要采取适当行动,其恢复能力很强。最先进的方法和现代研究工具证明了这一潜力,特别是在增加生物量和生物多样性方面。

- 绿色长城及其各类行动是改善萨赫勒地区状况的有效方法,但前提条件是将所有利益相关者(包括研究人员、管理人员和当地受益人群)密切联系起来。

新的发展协议目前正在利用跨学科的集体合作方针进行科学的测试,涉及研究人员、受影响人群和GGW从业者。这一工作旨在确定新的行动方案来提高人们适应变化的能力和创造新资源的能力,同时以平衡和可持续的方式管理环境。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:自2008年塞内加尔相思树首次移植9年后,塞内加尔“绿色长城”第一块再造林地鸟瞰图。[来源:照片©J-L Peiry,2017]

[1] DIFFENBAUGH NS, GIORGI F (2012). Climate change hotspots in the CMIP5 global climate model together. Climatic Change. 114(3-4):813-822. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-012-0570-x.

[2] NIANG I, RUPPEL OC, ABDRABO MA, et al (2014). Africa, in: BARROS VR, FIELD BC, DOKKEN DJ et al (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaption, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Reprot of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, pp. 1199-1265.

[3] PEIRY J-L and VOLDOIRE O. (2019) Climate framework and water resources in the Senegalese Great Green Wall area In: BOETSCH G, DUBOZ P., GUISSE A., SARR P. and. (Ed.). The Great Green Wall, an African response to climate change. CNRS Editions, Paris.

[4] LEBEL T, PANTHOU, G. & VISCHEL T. (2018)在萨赫勒地区,大旱灾后没有恢复正常。.See on The Conversation, URL: https://theconversation.com/au-sahel-pas-de-retour-a-la-normale-apres-la-grande-secheresse-106548 (in french)

[5] UN General Assembly, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html[accessed 21 August 2018]

[6] BOETSCH G, BOCCANFUSO P (2016)科学与绿色长城(电影)

[7] ROCKSTRÖM J, STEFFEN W, NOONE K et al (2009) A safe operation space for humanity. Nature 461: 472-475.

[8] NIANG K, SAGNA MB, NDIAYE et al (2014) Revisiting tree species availability and usage in the Ferlo region of Senegal: a rationale for indigenous tree planting strategies in the context of the Great Green Wall of the Sahara and Sahel Initiative. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences 2:529-537.

[9] WADE TI, NDIAYE O, MAUCLAIRE M et al (2018) Biodiversity field trials to inform reforestation and natural resource management strategies along the African Great Green Wall in Senegal. New Forests 49: 341-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11056-017-9623-3

[10] BOËTSCH G and SPÄNI A. (2013) The Great Green Wall: trees against the desert. Editions Privat, France

[11] BREMAN H, KESSLER JJ (1995) Woody plants in agro-ecosystems of semi-arid regions with an emphasis on Sahelian countries. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany

[12] SAGNA MB, NIANG K, GUISSE A, GOFFNER D (2014) Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile: geographical distribution and ethnobotanical knowledge by local populations in the Ferlo (north Senegal). Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Approximately. 18: 503-511

[13] NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL (2008) Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

[14] SAGNA MB, NDIAYE O, DIALLO A, GOFFNER D, GUISSE A (2014) Biochemical composition and nutritional value of Balanites aegyptiaca fruit pulp from the Ferlo region in northern Senegal. Afr J Biotechnol 13: 336-342.

[15] https://www.klorane.com/ch-fr/cheveux/dattier-du-desert

[16] DARDEL C. KERGOAT L, HIERNAUX P et al (2014) Re-greening Sahel: 30 years of remote sensing data and field observations (Mali, Niger) 140: 350-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.09.011

[17] http://future-sahel.blogspot.com/

[18] https://www.ilesdepaix.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Le-zaï-et-la-demi-lune.pdf

[19] http://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/3304

[20] https://rethink.earth/wayfinder/

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: GOFFNER Deborah, PEIRY Jean-Luc (2025年1月12日), 绿色长城:绿化萨赫勒的希望?, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年4月9日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/vivant-zh/green-wall-hope-greening-sahel/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。