Peatlands and marshes, remarkable wetlands

PDF

Peatlands are wetlands whose vegetation produces peat that is very rich in organic carbon. The quantity of water entering the system and its chemical quality determine many types of peatlands or mires: acidic sphagnum bogs, alkaline fens, reed and large sedges marshes. Biodiversity is remarkable: many habitats, flora and fauna often in decline or with very particular adaptations, for example insectivorous plants or animals resisting to the cold. It is often necessary to ensure its conservative management. In addition, mires have other important functions: flood and low-water level regulation, carbon storage, various productions – reeds, peat, game, extensive livestock farming – and educational showcase. Peat also provides an environmental record of past vegetation, climate change and the chronology of certain human activities for the last 12,000 years after the glaciations.

1. Place of peatlands in wetlands

The definition of wetlands is complex, as it varies according to time, users or countries. The Ramsar Convention (1971) has a broad definition:”wetlands are areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres.” [1]. It therefore includes coral reefs and Posidonia beds! These areas therefore form the interface between terrestrial ecosystems and the strictly aquatic ecosystems and are highly intertwined with them.

The definition of the French Environmental Code is more restrictive: they are “lands, exploited or not, usually flooded or gorged with fresh, salty or brackish water permanently or temporarily; vegetation, when it exists, is dominated by hygrophilous plants for at least part of the year” [2]. Both components are mentioned (water and characteristic vegetation), and a third – equally important – has been added to the application circulars: the nature of the soil, whose influence is fundamental.

Wetlands, important ecosystems to be conserved. From this introduction, it should be stressed that all wetlands play many fundamental roles in the overall functioning of the planet; this theme will be discussed below. For various reasons, wetlands have been severely affected by human activities for about two centuries and this is why, over the past half century, many study or conservation programmes have been set up, from the regional to the international level [4].

2. Nature of peat and functioning of peatlands

2.1. Peat is a carbon-containing organic material

Peat consists of at least 20 to 30%, sometimes much more, of poorly degraded organic matter. The latter comes from the accumulation, over centuries or millennia, of plant residues (Bryophytes and higher plants) in an environment that is always full of water [3].

This permanence of water, which is stagnant or not very mobile and therefore highly depleted of oxygen, inhibits the activity of microflora and strongly slows down the decomposition and recycling of plant debris that led to peat formation. Peat, very rich in carbon-containing compounds, is at the same time a humus, a soil (called histosol) and an imperfect sedimentary rock rather close to coal. It can be extracted, either to constitute a poor performing fuel, or to fertilize various crops during its slow degradation in a drier and more oxygenated environment [3].

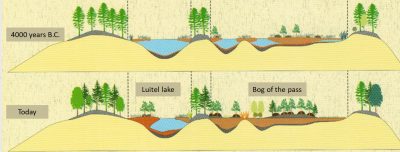

Peat forms from bottom to top, the oldest levels being at the bottom of the peat bog. The rate of accumulation varies greatly from region to region and period to period, but is at an overall average of 1 mm per year, i.e. 1 m per millennium. With few exceptions, Europe’s oldest current peatlands, which are about 11 to 12,000 years old, actually correspond to more than 10 m of peat.

We have also found, very well preserved in peat for millennia, sacrificed human corpses, such as Tollünd’s Man, in Denmark [10].

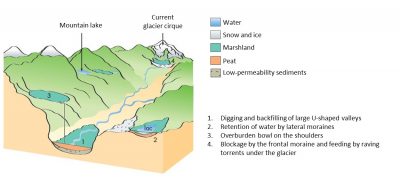

2.2. Distribution and origin of peatlands

The other type covers the mid- to fairly high latitudes of both hemispheres, in temperate or northern climates that are not too continental, with a higher density in Canada, the British Isles, Fennoscandia, the Baltic States and Russia, or -in the southern hemisphere- Patagonia, Chile and the Kerguelen Islands. At slightly lower and warmer latitudes, peatlands tend to take refuge in mountainous areas or oceanic areas; this is the case in France. These various regions have fairly moderate and highly variable temperatures over the seasons and receive between less than one metre to about two metres of annual precipitation. There are no mires in extreme climates, either desert that are too dry or very high latitudes and altitudes that are too cold.

The common point between these very varied peatlands is that enough water is needed to remain in the peat system; under a warm climate, a lot of rainfall is needed, while lower precipitation is sufficient under a cooler climate, because evapotranspiration is lower there. Other favourable factors are the topography and nature of the mineral subsoil; incoming water must be stored for a long time, without flowing too quickly downstream or into a porous substrate. There are peatlands locally on ridges or slopes, or in filtering areas, but then cloudiness or spring inputs are almost constant.

Peat conditions the peatland system and the peatland produces peat! A remarkable feature of peatlands is that the plants that live there build the peat bog themselves by gradually accumulating their debris on which they live; once the process is initiated, some plants give rise to peat and the presence of peat allows the presence of these plants. They are therefore self-constructed ecosystems, which can undergo several successive evolutionary phases.

2.3. Peatland diversity and evolution

In reality, the diversity of mires and peatlands is very important, especially in France and neighbouring countries [3]. It is impossible to present all these types of peatlands here; only two very different and representative examples will be explained.

In addition, France has various particular peat systems on the hills of the Armorican and Central Massifs, the Vosges or Corsica, without any initial body of water, or along the slopes in connection with seepage and springs or, again, in the back-littoral depressions of the sandy-silt coasts, from Dunkirk to Bayonne [3].

3. Peatlands and marshes are home to remarkable biodiversity

3.1. Each particular peaty habitat contains a special flora and fauna

The European Union protects its peatlands and their hosts. Many plant and animal species and habitats of wetlands, and of peatlands in particular, have become rare or threatened in Europe (Figure 9). The European Union’s Habitats-Fauna-Flora Directive (1992) lists these threatened species and habitats; there is then an obligation for all States to implement protection or conservation measures. The Muséum national d’histoire naturelle has published Directive-related documents on the species and habitats present in France [8].

Rather than lists of species or illusory statistics, some groups of peatland and marsh species of biological interest are presented below.

3.2. Example of plant adaptations to nutrition problems

If, in peatlands, there is nothing to prevent a normal photosynthesis for plants, the permanence and characteristics of water slow mineral nutrition (cations and nitrate ions); here are three examples of adaptation to these constraints [3].

Woody plants have developed another strategy for their nitrogen nutrition: symbiosis with other organisms. Thus, the Ericaceae (Figure 11) form underground mycorrhizae with various fungi capable of absorbing NH3+ ions which are toxic to most other plants, while the alder and the atlantic shrub Myrica gale host, in their root nodules, bacteria capable of directly fixing the molecular nitrogen dissolved in water (see Symbiosis & parasitism).

3.3. Some peatland animals [3]

Some lowland alkaline marshes still contain butterflies of the genus Maculinea (azuré in French). The three species typical azurés of marshes, which have become rare in Europe and are therefore included in the Habitats-Fauna-Flora Directive, are present in the Lavours Marsh [7]. One’s caterpillar feeds, at the beginning of its life, on Gentiana pneumonanthe flowers and those of the other two on the capitulas of the Sanguisorbus officinalis (Figure 13). In mid-summer, the caterpillars, a few mm long, fall to the ground where they can be recovered by ants of various Myrmica species. Thanks to chemical productions that are attractive to ants, caterpillars are introduced into anthills without being disturbed; they spend several months feeding on ants’ eggs and larvae before metamorphosing in July to complete their cycle. This multi-partners system is very fragile, because if the host plant or host ant disappears, the butterfly will also disappear.

4. Importance and roles of these ecosystems: Need to conserve them

Interest in biodiversity is fundamental (see above), as well as in various productions (reed harvesting, hunting, freshwater fishing, extensive livestock farming). Let us also recall the production of peat as well as environmental archiving and add historical, traditional cultural, recreational and educational aspects [3],[7].

It is estimated that, over the past 200 years or so, between 50 and 75% of peatlands (and other wetlands) have been destroyed or severely degraded in France and neighbouring countries. For peatlands, there are many causes:

– drainage for corn cultivation or poplar and conifers planting;

– industrial peat extraction that totally destroys the ecosystem;

– flooding to create ponds or hydroelectric dams;

– backfilling through landfills, the extension of urban areas or transport and energy infrastructures;

– various types of pollution, including latent eutrophication that accelerates the decomposition of peat.

A late awareness, sometimes thwarted by a strong inertia in decision-making, has emerged to conserve what remains and restore as many peatlands and marshes as possible [4]. In France, with respect to biodiversity and natural habitats, the so-called Pôle-relais national Tourbières in Besançon is responsible for collecting and disseminating knowledge and know-how to the various french managers such as natural parks, nature reserves, conservatories and various local authorities.

References and notes

Cover image. Lake Luitel (Isère, France) in autumn, with its floating mat with red sphagnum mosses. [Source: Photo © A. Lemercier]

[2] www.legifrance.gouv.fr/(Art. L.211-1) (in french)

[3] Manneville O., Vergne V., Villepoux O. et le Groupe d’Etudes des Tourbières (2006) 2e édition révisée. Le monde des tourbières et des marais. Delachaux & Niestle, 320 pages. (in french)

[4] Barnaud G. & Fustec E. (2007) Conserver les zones humides : Pourquoi ? Comment ? QUAE-EDUCAGRI, 296 p. (in french)

[5] Desplanque C. & Cave B. (2011) Réserve naturelle du Lac Luitel – livret-guide. ONF-Isère, 14 p. ; http://www.reserves-naturelles.org/lac-luitel (in french)

[6] Blanchard O. (2011) Tourbières – A l’épreuve du temps. Collection Montagnes du Jura, Néo éditions, CPIE du Haut-Doubs, 80 p. (in french)

[7] Collectif (1999) Entre Terre et Eau : Le Marais de Lavours. EID, Chindrieux,175 p. ; http://www.reserve-lavours.com/ (in french)

[8] Cahiers d’habitats Natura 2000, 2002-2004 : Tome 3- Habitats humides ; Tome 1/1- Habitats forestiers (certains sont tourbeux); Tome 6 – Espèces végétales ; Tome 7- Espèces animales. MNHN, La Documentation Française. Download on http://inpn.mnhn.fr/telechargement/documentation/natura2000/cahiers-habitats (in french)

[10] Anonyme (1997) Le peuple des tourbières (momies de l’Âge du fer). Sciences et Avenir, Septembre, p. 90-96 (in french) ; http://www.tollundman.dk/

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: MANNEVILLE Olivier (January 5, 2025), Peatlands and marshes, remarkable wetlands, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed April 5, 2025 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/life/peatlands-and-marshes-remarkable-wetlands/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.