什么是自然?

自然是一个常见的概念,如果不尝试去对其定义,每个人都熟悉“自然”。我们并不需要定义它,每个人都会熟悉它。这是正常的:对“自然”定义没有共识,这个术语被科学和人文领域的大多数学术学科都拒绝。然而,它仍然存在,而且更好的一点是它的政治意义非常突出,尤其是“保护自然”理念愈加迫切的当下。在这篇文章中,我们试图揭开自然的神秘面纱,追溯其起源、演变以及使自然处于中心位置的一系列问题。该文章旨在识别自然所包含的不同现实状况,以及人类在全球危机时代与之相处的具体方式。

1. 我们该如何定义“自然”?

极少百科全书有“自然”为题的文章。1751年,狄德罗和达朗贝尔在撰写文章时,就非常警惕“这个经常使用但缺少精确的定义并常被哲学家过度使用的词条”,原来负责该项目的布丰很快就放弃了。狄德罗和达朗贝尔紧急接替了布丰的工作,但他们也只提供一份有限的目录,“其含义如此之多,一位作者可以数到14或15个”缩小版目录,这篇文章包括对术语的交叉引用,尽管这些术语五花八门,如“世界体系”、“原因”、“本质”“天意”,甚至“上帝”(图1)。

即使在今天,专业的百科全书似乎仍然谨慎地回避“自然”这一概念,例如,《牛津科学词典》(2005年版)和《环境伦理与哲学百科全书》(2008年版)。《生态与环境科学百科全书》给出了三行似是而非的文字,《生态思想词典》(2015版)则谨慎地限定了文章讨论范畴(“哲学中的自然”、“普通自然”),绕过了自然本身——但是在许多文章中都得到引用。在哲学领域情况相似,自然并不是主流大学教科书中的“哲学主要观念”,也从未出现在任何法语考试或竞赛的大纲中。安德烈·拉兰德的《词汇技术与哲学批判》(Vocabulaire Technical et Commission de la Phology)是为数不多的提及自然的教科书(自1902年以来定期更新),也效仿了达朗贝尔的做法,建议严谨的思想家避免使用这一词条,因为这个词可能意味着任一可能性,也可能意味着其相反一面。此外,许多科学家公开回避这一词语,他们更喜欢定义更明确且可测量的下位词——比如人类学家提出的“生物圈”、“生物多样性”、“生物群落”、“生态系统”和其他“物理性”。在当下,没有量化,就不是科学。

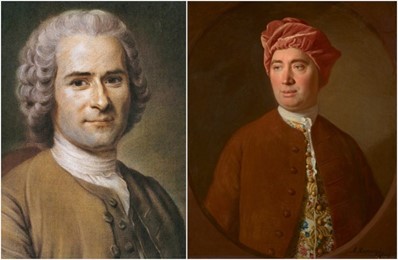

[资料来源:《让-雅克·卢梭》(1753),莫里斯·康坦·德·拉图尔

(Maurice Quentin de La Tour)粉彩画;《大卫·休谟》为艾伦·拉姆齐(Allan Ramsay),知识共享组织(Creative Commons)公共领域发布]

因此,“自然”(nature)在欧洲语言中本质上仍然是一个“随意”的术语,除了与“human”结合为“human nature”(人性)之外,几乎从来没有成为先进学术理论的主题,唯一的高光时刻是18世纪在戴维·休谟和让-雅克·卢梭[1](图2)的推动下有过短暂的辉煌。

然而,生态危机使自然的概念重新成为人们关注的焦点,这个词现在无处不在。这一事实表明,自然可能并不意味着“虚无”,也不可能被替代。当自然被称为“处于危机中”,当每个人都想“保护”自然甚至“采取行动”时,对这一概念及其后果的清晰认识比以往任何时候都要迫切,而这正是撰写本文的目的[2]。

2. 一个神秘单词的故事

[来源:让-路易斯·马齐埃尔斯(Jean-Louis Mazières)照片©CC BY-NC-SA 2.0]

词源学通常是阐明一个术语深度的极好方法;然而,“自然”一词在很大程度上脱离了这种方法。Nature(英文中的“自然”)一词源自拉丁语动词nascor,意思是“出生”,作为拉丁语中的其中一类动词(supine),这种形式可以用来构建未来分词(但似乎在这里不适用,至少没有这种意义上的用法),或者像其他以-ure结尾的拉丁语单词,比如culture(文化),temperature(温度),表示一种存在方式。因此,从词源学上讲,它指的人类诞生的方式,一种原始的特征——这就排除任何绝对的用法(实际上在整个前古典时期是不存在的)。在古典时代,当来自优越家庭的年轻罗马人去希腊完成知识教育时,这个词被选来翻译希腊语的phusis,并成为它的标准翻译。

Phusis是希腊哲学中最复杂的概念之一,即无所不在。几乎所有前苏格拉底时期的哲学家著作都以“Peri phuseos”(Phusis 的变体,意为“论自然”)为标题。这个概念成为了所有科学或哲学事业的对象,但是其含义和用法在不同的作者之间有巨大的差异,或者更准确地说,在不同的哲学流派之间存在差异。在希腊的鼎盛时期末,亚里士多德试图对这些含义进行编目,并列出四个主要的含义[3]:

- 生长之物的生长;

- 生长之物最初的内在因素;

- 自然之物的运动原则;

- 任何物体的源头存在以及任何人造物体产生或来源的原始背景。

这四个定义可以粗略地概括为:成长、原则、力量和实质。因此,我们在这里进入物理学领域–在偶然机会下创造“physics”(物理学)这个术语——但仍然远远未触及生物学和环境。希腊-罗马语言中的“自然”还不是指一组物体,而是指赋予物质生命的动力学,无论是否有生命的物质都适用(这个词在哲学家的生物书中不常使用)。

事实上,后来是欧洲的基督教化改变了“自然”一词的含义。在基督教实际的宇宙观中(图3),所有的动力只能来自于上帝,只有他创造世界,并赋予其生命,他超越了自然,没有什么能超越他——而在希腊,众神服从自然,他们仍然以动物的独特形式存在,受到冲动、激情和需求的驱使。在亚伯拉罕一神教中,整个现实世界只是一种创造物,是由造物主构思和安排的一组被动物体,只有人类才会从中出现,人类既是这种创造的一部分,但又被要求超越它。这种等级制度是一个极其原始的观念,似乎在任何其他伟大的文明流域中都没有出现:这么一来,人类不再完全是自然的一部分, 人类存在的所有价值超越自然,在上帝的国度中。因此,不再有“创造自然的自然”(natura naturans),一个等同于上帝造物的原则,也不再有“被自然所创造的自然”(Natura Naturata),等同于上帝的创造。忠诚的基督徒必须鄙视世俗的东西[4],因为要通过禁欲才能最终进入天堂。因此,“自然”这个词在中世纪很少再使用,又回到其词源学的用法。

老布鲁格尔(Bruegel the Elder)的桌子。画面中间代表了“大自然母亲”,,即伊希斯的母亲形象,胸部有许多乳房。[来源:Peter Paul Rubens,在维基公共媒体的公共领域发布]

直到文艺复兴时期,随着对古代文献重新被发现,欧洲知识界开始重新审视“自然”,但没有对其意义进行理论化。自然被视为创造的整体(或包括人或不包括),即调节世界的一组物理力量(“自然法则”),或者是一种抽象的现实力量,有时意味着一种神圣意志的尘世使者,甚至是全能之父的仁慈的女性化身(古典时代晚期,自然已经成为寓言中的一部分,是伊希斯(Isis)的母亲形象的一部分,后来被世俗化为“大自然母亲”的概念[5])(图4)然而,杰出的形而上学哲学家柏拉图似乎对这个概念没兴趣,这一概念过于物质化,而在古典时代,哲学界逐渐确立了柏拉图作为哲学概念仲裁者的地位,这可能也导致后来大多数欧洲学术传统领域对“自然”嗤之以鼻,并延续至今。

3. “自然”一词用法的多样性

尽管学术界不喜欢“自然”这个词,但在法语常用字典中的60000个单词中,“自然”在使用最频繁的单词中排第419位。在浪漫主义时期以及西方20世纪60-70年代的文化运动中,“自然”经历了一些短暂的兴起,尤其是因为它本质上的颠覆性,“自然”和“文化”之间的对立使其成为挑战既定秩序(“回归自然”)的完美手段——尽管“既定秩序”也正是“自然”的含义之一[6]……

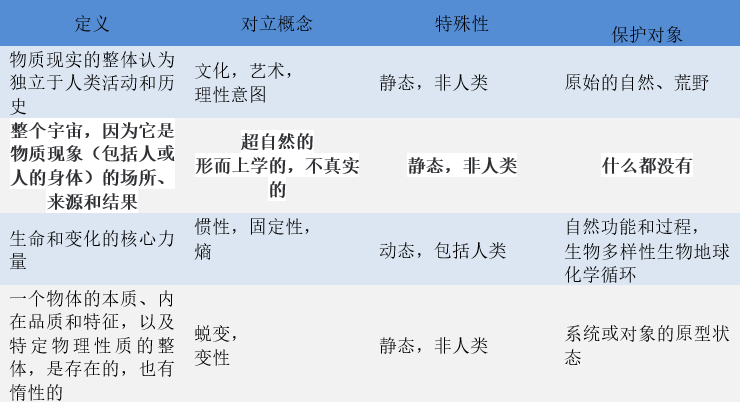

2020年发表的一项研究[7]通过查阅不同词典,尝试梳理“自然”一词的含义和用法,其中一些词典对“自然”有多达20种不同的且相互矛盾的定义。所有这些对自然的定义可以总结为四个主要观点:

- 非人类意志所产生的物质现实的总和(与技巧、意图和文化相对立);

- 作为物质现象的场所、来源和结果的整个宇宙,包括人或至少是人的身体(与超自然、形而上学或虚幻相对立);

- 生命和变化原理下的力(与惯性、固定性和熵相对立[8]);

- 本质,物体特定的物理属性和特质的集合,有生命的或惰性的(与变性相对立)。

这四个定义在许多方面都极不相同:一些包括人类,而另一些明确的排除人类;一些定义是指客观对象,另一些定义是指抽象的现象或特征。因此,这些定义可以构成根本不同甚至是相互矛盾的“自然保护”的基础,甚至对某些人来说,使“自然保护”变得荒谬:表1将这些定义及其自然保护方面可能代表的内容进行了归类。

4. 保护什么?

正如我们所见,自然具有多重意义,因此,保护自然也出现不同的分支,它们随着新问题出现的速度在不断叠加推进,并非接替出现。

4.1. 将自然作为一系列资源进行保护

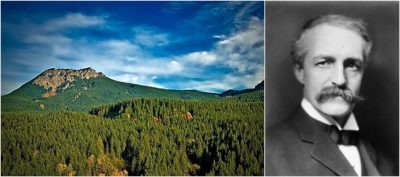

纵观历史,“自然”本身过于抽象和庞大,无法成为人类直接行动的对象,人类社会首先保护的是自然“资源”(木材、猎物、“有用的”动植物……)[9]。早在中石器时代,定居生活的人类就开始存储部分资源,以确保其繁殖和长期生存存在。这种管理模式后来委托给专门的组织。例如在法国,菲利普·勒·贝尔在1291年创建了水资源管理局和森林管理局(1669年由让-巴蒂斯特·柯尔贝尔进行现代化改革)由 。19世纪末在美国,面对伐木产业疯狂增长的需求,吉福德·平肖(在法国南锡国立高等矿业学校接受教育)在自然资源保护方面做出了伟大贡献。伟大的自然资源保护者(图5)。

4.2. 将自然作为生活环境进行保护

人们在定居生活中产生了健康和安全的观念。人类居住区吸引大量的共生或寄生物种,包括动物、植物甚至细菌,但物种并不总是有利于人类生活。因此,生存环境的组织管理迅速成为所有人类社会的必要条件,最突出的就是消灭一定数量的不受欢迎的动物,通常是通过家养的猎食动物杀灭(比如狗、猫、鼬科动物、灵猫科动物、鸡等),后来也使用杀虫剂杀灭。随之而来的是景观的人类化,首先出现的是形态变化(沟渠、梯田、农田)和植物变化(果树、观赏树木、篱笆)。这种全新而舒适的生活环境很快成为定义自然的标准,但却是有人为耕种和驯化痕迹的自然,与被认为充满敌意和危险的野生自然截然相反。因此,这种自然纯粹是一种社会生态系统,一种自然思想,一种供人类活动发生的环境,在很大程度上与其他自然概念相违背。这正是拉丁游牧过去所称的“愉快的地方”(locus amoenus),一种自然花园(图6)。这种理想在园艺、景观美化和城市规划的历史中也确实存在,特别是在19世纪城市公园的建设潮流中(比如建于1820年的海德公园建于,建于1852年的布洛涅森林公园年,建于1869年的中央公园建于)。由于这是一个理想,可以把它与自然的第四个定义相连,即规范性原型状态。

保护这个美丽且具有审美意义的自然环境被称为环境保护主义,这一术语蕴含了人类中心主义的维度,应该与生态主义区分开来。事实上,这归根到底是一个保护人类的问题,首先是保护人类免受野生自然的侵害,很快发展成应对人类自身的妨害行为。正因如此,阻止妨害行为的规定出台,包括古代的下水道和厕所的建造,工业革命中更重要的措施(图7) :例如,法国在1810年10月15日发布关于”散布不健康或不良气味的制造业和作坊”的帝国法令,以及英国在1815年创建公共空间和人行道保护协会。大多数早期的环境法都属于这一框架,保护一种特殊状态的“自然”,即驯化且被人类支持的自然——也因此具有一定合理性。

4.3. 将自然作为纪念碑和景观进行保护

自然的概念在18世纪经历一场革命。西方人完成了整个地球的地图绘制工作,突然之间地球看起来出奇的小。与此同时,探险家们对不同物种的空间分布有了概念,认识到其中一些物种已经彻底消失。而在此之前,人们的想象中似乎任何物种都存在其他剩余的种群(包括成为化石的物种,图8)。人们开始意识到,上帝似乎并不会“重新创造”人类已经摧毁的创造物,而且随着第一代浪漫主义者的出现,上帝与自然的关系突然发生变化:自然从无限富饶的神秘之母转变为人类历史上脆弱的战场。

因此,在19世纪工业革命的影响下,“保护自然”的思想在西方逐渐萌芽——这一次,主要是艺术家、知识分子和作家为这一运动做出了贡献,如法国的查尔斯·博基耶或美国的约翰·缪尔。此处需要再次使用第四个基本定义:自然保护涉及一个地点的原生状态,通过各类管理方法(国家公园、自然纪念碑、遗址等)尽力保持其原貌。因此,当时壮丽的自然景观和具有生物或地质特征的地点受到重点保护,包括美国黄石的间歇泉(图9)以及殖民地狩猎保护区;还有枫丹白露森林,1861年因巴比松学派的自然主义画家而获得保护,被称为“艺术系列”,因为这是巴黎周边最后一个可以欣赏古树的地方。因此,这种“自然”本质上是一种景观环境受到保护,但这一回不是直接用作生活环境的自然,而是具有美学和智力价值的自然。还有一种观点认为,这些地方必须受到保护,不受文明的玷污,这与第一个定义不谋而合。在美国,这一定义后来走向极端,将荒野视为天堂的形象,因为它保留了上帝创造的原貌,没有被人类的活动所破坏[10]。与此同时,民族主义思潮的诞生以一种特别明显的身份认同方式巩固对自然遗产的保护[11]。在19世纪末,对象征性物种的保护也具有相似的理念。

4.4. 将自然作为一套生态系统进行保护

1935年生态系统概念的出现,“自然”作为科学研究对象的观点才得到更新,首先是作为科学研究对象,然后是作为保护对象。虽然自然资源保护主义的传统是固定论,集中于不活跃或变化微小的物体(或者至少被当作这样对待) ,但在达尔文的推动下,一种更具活力的自然观得到发展,肯定了前文中第三个定义。这种转变的守护者之一是著名的美国森林学家奥尔多·利奥波德,他的著作《沙乡年鉴》在逝世后才得以出版,被认为是美国生态学的“圣经”。虽然利奥波德对生态系统这个术语还不熟悉,但他仍然呼吁积极保护“生物群落”,后来(1992年)更名为“生物多样性”。利奥波德帮助建立了未开发森林保护区,不是出于美学或旅游资源的考虑,而是其生物和生态重要性,这与国家公园的保护形成鲜明对比——在此之前设立的国家公园几乎都位于干旱地区或山区。

因此,这种将自然视为一套生态系统的全新保护方法本质上是基于科学标准所设立,如生物多样性、地方特有种和生态功能——这开启了“普通自然”的保护,因为,这些主要功能在很大程度上依赖于最丰富的物种[12]。生物功能、物质流(水、碳、氮)和能源等抽象概念也将发挥作用。它们对人类社会的重要性得以体现在2005年《千年生态系统评估报告》中所普及的“生态系统服务”概念,该报告由联合国于2000年委托编写[13]。大自然不再是惰性或被动的,而是正在成为生物群落之间交流的平台,人类是其中一个行为者,强大但也具有脆弱性和依赖性。

4.5. 将自然作为我们所知的有利于生命的环境进行保护

因此,21世纪自然保护的新挑战是保护处于人为化空间的核心地带的自然(人为化空间现在已经基本覆盖地球),以及保护穿越人为化空间的物质流——这就是一些人所说的“人类世”[15]。除了仔细保护最后剩余的未开发生态系统外,这一新的自然保护工作还必须关注社会生态系统,这些生态系统包含了各种各样的人类、非人类、生物和非生物因素,所有这些因素都保持着复杂的关系(请阅读《生物多样性不是奢侈品,而是必需品》)。面对这一“自然”的方法之一被称为“和解生态学”[16],它旨在通过一系列技术和发展使人为化空间有利于生物多样性。还必须重新思考农业,避免农业发展形成更多富含有毒物质的沙漠,让农业成为保护生物多样性的港湾,维系土壤质量,保护植被健康,造福农业地区人民[17]。

因此,除了技术和管理方面的挑战外,我们还在见证一场真正的哲学革命:自然不再是“局外人”,关注自然与关注人类群体之间的界限正在逐渐消失,在此之前,这个界限导致西方对自然科学和人文科学有着严格的区分。因此,与这种认识论的剧变伴随出现的是一种新的哲学成果,这种哲学成果的代表人物有美国的J·贝尔德·卡利科特、法国的人类学家菲利普德·斯科拉、社会学家布鲁诺·拉图、哲学家凯瑟琳·拉雷尔等,他们被归类为“环境人文学科”的学者。

5. 重要信息

- “自然”的概念理解起来特别复杂,在历史发展过程中经历了巨大的演变。在今天,对自然有四个主要定义,但也极为不同,甚至存在矛盾;自然是:

-

- 非人类意志所产生的物质现实的总和(与技巧、意图和文化相对立);

- 作为物质现象的场所、来源和结果的整个宇宙,包括人或至少是人的身体(与超自然、形而上学或虚幻相对立);

- 生命和变化原理下的力(与惯性、固定性和熵相对立[8]);

- 本质,物体特定的物理属性和特质的集合,有生命的或惰性的(与变性相对立)。

- “保护自然”的概念因所使用的定义框架不同而不同,各种自然保护传统随着时间的推移而发展,其对象、技术、概念和目标各不相同,在这里也很容易相互矛盾。

- 围绕着“自然”概念的模糊性阻碍了它在某个特定学科领域(哲学、生物学、政治学… …)得到恢复与发展,迫使科学界和各类机构开始面对这个内涵丰富且传递出许多社会影响的词语。

- 这一多样性通过维持多样的选择和民主对话的机会阻止了“自然”的技术官僚化。

- 在这篇文章中,我们仅讨论了“西方”的“自然”概念,但它在其他语言中的对等含义(或缺乏对等)是2020年发表的一项研究的主题[18]。

附注及参考资料

封面图片。[来源:照片©Frédéric Ducarme]

[1] 我们在此不讨论这种用法,而是参考吉恩·埃拉尔(Jean Ehrard)的作品,特别是法国新世纪初期的《自然之光》,巴黎:Albin Michel,1963年,或者参考被加纳·弗拉马利昂(Garner Flammarion)收录在文集中的弗兰克-布尔巴奇(Franck Burbage)的《自然》一文。

[2] 本文的主要灵感来源于作者的博士论文(于2016年在国家自然历史博物馆完成答辩)以及后续出版的两篇文章:Ducarme F,Couvet d.(2020年)《“自然”是什么意思?》自然人文社会科学通讯,6(14):1-8。DOI:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y;Ducarme F,Flipo,F.,Couvet D.(2020年)《人类自然概念的多样性如何影响生物多样性保护》,《保护生物学》,34(5),DOI:10.1111/cobi.13639。

[3] 亚里士多德,《形而上学》 ,第4期,第1014b 页。

[4] 马太福音6:19。

[5] Hadot P. Le Voile d’Isis。巴黎: Gallimard,Folio essais;2004年,第515页。

[6] 关于在道德语境中对自然概念的(错误)使用,参考文献无疑是John Stuart Mill在三篇关于宗教的论文中的《论自然》。伦敦:朗文格林;1874年

[7] Ducarme F,Couvet D.(2020年)“自然”是什么意思?《自然人文社会科学通讯》,6(14):1-8。DOI: 10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y

[8] 注意,这里熵的概念不是从天体物理学的意义上来理解,而是从普遍的意义上来理解,而且是在极小的尺度上,即趋于消散的能量或趋于贫乏的生态系统的能量。

[9] Ducarme F.(2020),《自然与自然保护历史的演变与嬗变》,自然保护研究会,法国国家档案馆,巴黎,2020年9月29日至30日。

[10] 由罗德里克·纳什(Roderick Nash)进行理论化的关于“荒野”的概念,(《荒野与美国思想》:耶鲁大学出版社;1967年),常出现于柯倍德(J. Baird Callicott)的许多作品(如《伟大的新荒野辩论》)。乔治亚大学出版社;1998年, 第697页)。

[11] Luigi Piccioni(2014),“欧洲美好年代景观和自然遗产发展的概念工具”,“景观工程”,专题“景观和遗产:知识、保护、管理和提升”,https://journals.openedition.org/paysage/11109。

[12] 关于这一表达方式,请参见Catherine Larrère或Rémi Beau的作品,如Beau R,《普通自然》,Bourg D,Papaux A《生态学词典》。巴黎:PUF;2015年

[13] 千年生态系统评估:生态系统与人类福祉。华盛顿特区:世界资源研究所;2005年

[14] Phalan B、Onial M、Balmford A、Green RE。协调粮食生产和生物多样性保护:比较土地共享和节约土地。科学2011年;第333页(9月):1289-191年。

[15] Lewis SL,Maslin MA。定义人类世。《自然》杂志2015年;第519页(7542):171-80.

[16] Rosenzweig ML.,《共赢生态学:地球物种如何在人类事业中生存》。牛津:牛津大学出版社;2003年。有关法语摘要,请参见Couvet D、Ducarme F.L’écologie de la réConference、du Défi biologique au Défi social。民族生态学杂志。2014年;6:13.

[17] Butler SJSJ,Vickery JAJA,Norris K.农田生物多样性和农业足迹。《科学》,2007年;315:381-4.

[18] Ducarme,F.,Flipo,F.和Couvet,D.(2020),“人类自然概念的多样性如何影响生物多样性的保护”,《保护生物学》34:6,doi:10.1111/cobi.13639

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: DUCARME Frédéric (2024年3月13日), 什么是自然?, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年4月12日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/vivant-zh/what-is-nature/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。