Economic theory and environment : a divorce ?

PDF

Not a day goes by without the media denouncing the damage to the natural environment of our societies and these misdeeds being attributed to the malfunctions of the economies. Would they be unable to develop without wasting natural resources and endangering biodiversity or human health ? The accused: choices of production and consumption. Is this trial justified ? Are the environmental impacts due to insufficient compliance with the requirements of the economic analysis? Any attempt to answer this question requires a clear understanding not only of the nature of the relationship between economic activity and the environment, but also of the ways in which it evolves. Is the economic analysis really interested in them ? Over time, has it progressed towards greater openness or has it tended to withdraw into itself ? Are its conclusions consistent with the requirements of sustainable development ?

- 1. Natural resources absorbed by economic activity

- 2. Discharges of economic activity into natural environments

- 3. The effects of technological change

- 4. The societal dimension of economic-environmental relations

- 5. The environment in the evolution of economic thinking

- 6. A little history: from the first beginnings to Mercantilism

- 7. The French Physiocrats

- 8. The English Classics

- 9. Neo-classicals completely separate Economics from the environment

- 10. Message to remember

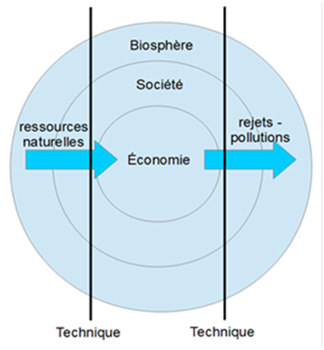

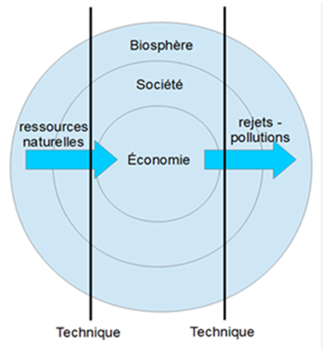

1. Natural resources absorbed by economic activity

Whether local, regional or national, all economies bear the marks of their natural environment : climate, relief, hydrography or soil quality. All other things being equal, production or consumption in the tropics differs from that in the temperate region. However, these influences are too diffuse for economic analysis to include them in production or consumption functions.

The quantity, quality and accessibility of these resources obviously influence production conditions, the costs of finished products, the competitiveness of companies, consumption and the structures of economies. To be convinced, it is enough to compare the characteristics of Japan’s economy, which is poor in all types of natural resources, with those of Saudi Arabia, whose subsoil is full of crude oil. In the Netherlands, the sudden wealth due to the exploitation of Groningen’s natural gas from 1959 onwards even caused a collapse of part of the economy (Figure 2).

2. Discharges of economic activity into natural environments

Linked to their natural environment by their withdrawals, economies are also linked by what they discharge into it in the form of solid, liquid or gaseous waste. Some of them are absorbed and regenerated naturally, others cannot be for reasons of quality or quantity. They are then likely to threaten the quality of natural environments, with collective damage to living resources, health and the economy, the composition of the lithosphere, the hydrosphere and the atmosphere. The urban pollution of the latter by plant smoke is well known, although its cost in terms of building degradation and public health is not always easy to estimate.

Until the end of the 20th century, because of their productive structures, some national economies could feel relatively sheltered from the nuisances associated with local pollution. This has not been the case since the identification of global releases : vortexes of waste from the Pacific Ocean (http: plastic pollution of the oceans), CFC gases and methylene chloride threatening the ozone layer above the poles, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, source of global warming, long-lived radioactive waste.

To varying degrees, these discharges affect economies through their impacts on their environments. Some increase the production costs of companies forced to eliminate them or pay taxes to the entities that do so. Others, more worrying, could eventually completely paralyse economic activity due to the disruption of the balance of certain ecosystems.

3. The effects of technological change

The dual family of economic-environmental interactions (resource extraction and discharges) has varied considerably over time, and still varies spatially, as a result of technological change. Most of the latter have tended to intensify relations through a sustained growth in resource extraction, particularly following the first two industrial revolutions, whose emblematic technologies (coke steel and steam engine, then internal combustion engine and thermoelectricity) have caused massive extraction of ferrous ores, coal and hydrocarbons.

Some technological changes, on the other hand, stopped the degradation of part of the environment: the expansion of coal mines from the 18th century onwards saved what remained of the forest in Western Europe; a century later, access to oil resources stopped the extinction of whales by replacing the use of their fat with mineral oil; at the end of the 20th century, clean heating techniques allowed London to get rid of part of its smog [2]. In the 21st century, advances in energy efficiency, solar photovoltaic and electricity storage technologies are likely to help limit GHG emissions.

4. The societal dimension of economic-environmental relations

In fact, not all societies between countries with comparable per capita incomes are equally sensitive to changes in their environment for cultural reasons. Moreover, not all of them have a productive and institutional organization capable of redirecting technological change in a way that is compatible with environmental protection. What China is doing in this area is not within the reach of its Southeast Asian neighbours! More generally, ecological awareness is not also developed in all countries.

5. The environment in the evolution of economic thinking

6. A little history: from the first beginnings to Mercantilism

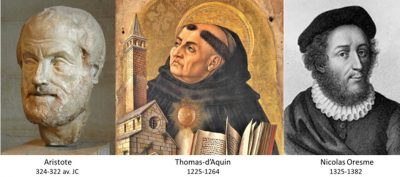

The first known ideas on the economy date back to Mesopotamian texts, then, later, Chinese or Indian, before those of Greek philosophers, from Democritus or Xenophon to Aristotle : the notions of trade, market, prices or taxation emerge which concern only a tiny part of an economic activity consisting of primitive agriculture and crafts already affecting natural ecosystems by deforestation in the most populated regions, such as the Mediterranean shores [3].

During the European Middle Ages, and more particularly during the 13th century, economic thought began to emancipate itself from the philosophical and even theological context from which it was inseparable. At least two developments allow it : on the one hand, some philosophers are reviving the Aristotelian conception of knowledge ; on the other hand, great economic upheavals are emerging from the expansion of trade, punctuated by major fairs, then extended by the opening of Europe to new continents, including Asia and its silk route. Scholastics, based on the writings of a Thomas Aquinas or Nicolas Oresme, discuss the fair price of commodities and the legitimacy of the interest rate (Figure 5). In Spain, the Salamanca School is further expanding this field by justifying the free movement of persons and goods, legitimizing private property, and laying the foundations for a theory of money and (subjective) value.

Nor are these subjects of interest to the Mercantilists who succeeded the Scholastics from the 16th century onwards [5]. With the discovery of the New World, the influx of precious metals into Spain and the strengthening of monarchies, economic thinking is focusing on the enrichment of states through the accumulation of currency, resulting from the trade balance surplus achieved through protectionism and export support. Some Renaissance men, such as Ronsard in “L’Élégie contre les bûcherons de la forêt de Gâtine”, are well aware of the degradation of their environment, but very few establish a link between this state of affairs and the enrichment of European societies [6].

7. The French Physiocrats

About a century later, things seem to be on the verge of change since economic thought is now represented by a School whose name “Physiocracy” means no less than government (kratos) of nature (physis) [7]. The latter is, according to the physiocrats, the source of the gross product provided by the mines, which “are certainly a new wealth for the nation” and of the net product from agriculture “because a field produces fruit every year”. Why this difference ? Because “agriculture allows a multiplication where other activities only add up”. It is the source of all the wealth of the State and its citizens. “Only the Earth restores to man more value than it receives from him” [8].

Especially in France, the home of the Physiocrats, this transfer of the foundations of the wealth of trade to agriculture reflects the rapid progress of agriculture, under the effect, among other things, of the advances in agronomy from which some large landowners know how to benefit. In doing so, the human economy has been placed back in the economy of nature. This is illustrated by the publication of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s “Études de la nature” [10].

8. The English Classics

Less than twenty years have passed between François Quesnay’s “Tableau économique” (1758) and Adam Smith‘s “Recherches sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations” (1776) that economic thought is turning its back on nature once again, even though several developments should have prolonged physiocratic ideas.

The 18th century, “especially in its end, marks the height of a strong interest in nature; although the link between nature and God has not yet been broken, nature is gradually becoming the object of science alone” [11]. This is illustrated by the first edition in 1735 of Carl von Linné’s “Systema Naturae” (1707-1778), which proposes an “economy of nature” that applies to all three kingdoms, mineral, vegetable and animal. Its main critic in France, the Count of Buffon (1707-1788), widely disseminated all the knowledge of the natural sciences of the time [12].

But the 18th century was also the birth of the First Industrial Revolution, between the transition from cast iron to Abraham Darby’s mineral coal coke (1709) and James Watt’s steam engine (1776), an unprecedented expansion of coal mines whose low extraction costs contributed to England’s economic growth. As a counterpart to this development, a degradation of natural environments caused John Ruskin’s (1819-1900) indignation.

However, not all the economists at this classical school break as completely the links between economic activity and its environment. For Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834), nature, generous in life germs for plants and animals, is thrifty in place and the food they need to live, hence a struggle for life leading to limits assigned to each species [14]. Men cannot escape this law : a population growing according to a geometric progression (it doubles every 25 years) will inevitably come up against the limits of an increasing agricultural production according to an arithmetic progression. Poverty is not the result of economic institutions but of the greed of the earth, which can only be fought through abstinence and chastity.

David Ricardo (1772-1823) nuances the Malthusian analysis by specifying that the avarice of the earth is heterogeneous. Consequently, the growth in food needs encourages people to cultivate less and less fertile land, which in turn leads to higher production costs. Unlike industry, which has no ecological limits, agricultural activities are subject to the law of diminishing yields, which also applies to mining activities. “Nature makes its services pay all the more for the higher the demand for them,” François Divisia concluded in his “Rational Economy” in 1928, unless, he was told, technological progress pushes the limits of nature !

9. Neo-classicals completely separate Economics from the environment

The openness of some English economists to the environment will be short-lived. Even as Ecology took off with Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), the Economy cut its last links with the environment and withdrew into itself thanks to the success of the Neoclassical School.

Since Karl Marx turned the labour value of the Classics against liberalism, the idea of a paradigm shift has been advancing. Between 1871 and 1874, William Stanley Jevons (1835-1882) in Manchester, Carl Menger (1840-1921) in Vienna and Léon Walras (1834-1910) in Lausanne founded the so-called Neoclassical School because it was part of Adam Smith’s descendants, but she proposed to base the value of the goods on the value-in-use resulting from a marginal analysis. Beyond their differences, the members of the new School share the idea that “for each agent, the value of each unit of a good is all the lower as the total quantity he owns is higher, and that it is from these “marginal” values of an additional unit that exchanges determine prices” [15]. This determination under a system of absolute competition, as well as the conditions for general economic equilibrium resulting from it, define the scope of the Economy. The latter, particularly in Léon Walras’ work, must take as its model the physical sciences, more precisely rational mechanics.

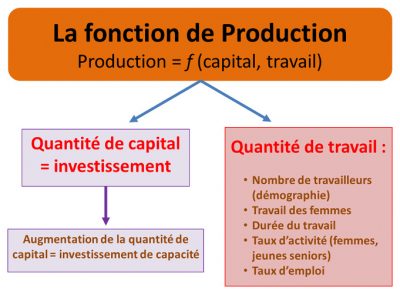

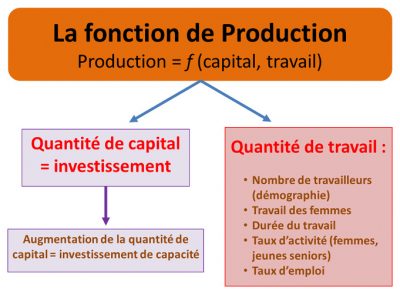

For these economists and their successors, who constitute the dominant economic thought in the 20th century, the natural environment, like technology, belongs to the world of data and therefore does not fall within its scope. This is evidenced by the elimination of the “land” factor from the production function, which is now limited to labour and capital (Figure 8).

Although far from these epistemological foundations, the other great economists of this period did not bridge the gap : John-Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), because he was too concerned about finding an explanation for the great economic crisis of the 1930s; Joseph Aloys Schumpeter (1883-1950), because he wanted to integrate market analyses into a structural approach in which technological progress was the driving force.

10. Message to remember

Faced with the environmental impacts that accompany global economic growth, especially after the Second World War, economic thinking has stalled. To get out of it, it will have to, within the epistemological framework forged from the end of the 19th century, invent rules to answer the two main questions that link the economy and the environment:

- what is the true price of natural resources

- what is the real cost of pollution ? (Read “Economic theory in the face of environmental realities”).

References and notes

Cover image. Diverging trends in the respective needs of the economy and the environment. [Source: original creation © Encyclopedia of the Environment]

[1] The term “environment” refers to all the natural and cultural conditions in which living organisms, and man in particular, develop, hence the need to qualify as “natural” when only its physical, chemical or biological aspects are considered. For the sake of simplicity in the text below, this qualifier will be neglected.

[2] Martin Jean-Marie (1990). The global energy economy. Paris : La Découverte, 126 p (pp. 33-59).

[3] Cipolla Carlo M. (1974). Storia economica dell’Europa pre-industriale. Bologna: Il Mulino, 349 p.

[4] Gimpel Jean (1975). The industrial revolution of the Middle Ages. Paris : Editions du Seuil, 246 p.

[5] With the exception of one of the last representatives of this School, Richard Cantillon (1680-1734) according to whom “the value of things derives from the earth and work”, but especially from the earth. Albertini Jean-Marie, Silem Ahmed (1983). Understand economic theories. Paris : Editions du Seuil, 643 p, (p. 593). This same book gives an overview of Mercantilism in Europe: bullionism in Spain, colbertism in France, commercialism in England and the Netherlands (pp. 79-81).

[6] Acot Pascal (1988). History of ecology. Paris: PUF, 283 p.

[7] A list of its members and their publications can be found in the section dedicated to the Physiocrats Romeuf Jean, under the direction of. (1958). Dictionary of economics. Paris: PUF, 1,198 p.

[8] Cours d’Economie Politique de Turgot (1727-1781), quoted by Jean Romeuf, Dictionnaire, op. cit., p. 869.

[9] Vivien Franck-Dominique (1994). Economy and ecology. Paris : La Découverte, 122 p (p. 17. The following quotations are taken from the same book.

[10] Bernardin de Saint Pierre (1737-1814) is best known for his novel Paul et Virginie (1788). His Études de la nature (1784) is still available, in its 1840 edition, from Price Minister.

[11] Deléage Jean-Paul (1991). History of ecology, a science of man and nature. Paris : La Découverte, 330 p (p. 33).

[12] Les sciences de la Nature au Siècle des Lumières en France et en Europe, in Soboul A., Lemarchand G., Fogel M. (1977). The Age of Enlightenment. Paris: PUF.

[13] Polanyi Karl (2009). The Great Transformation. Paris: Gallimard, 467 p (pp. 171-72). The beginning of the text in quotation marks is taken from “The Wealth of Nations” without precise reference.

[14] In Essai sur le principe de population, French translation, p. 68.

[15] Dréan Gérard. Another story, 2, op. cit.

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: MARTIN-AMOUROUX Jean-Marie, CRIQUI Patrick (February 10, 2019), Economic theory and environment : a divorce ?, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed December 21, 2024 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/economic-theory-and-environment-divorce/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.