Multi-purpose river development: example of the Rhone River

PDF

In 1933, the Compagnie Nationale du Rhone was created in response to specific needs such as generating electricity, developing navigation and promoting irrigation. New uses then appeared, particularly in connection with the development of leisure activities. Since thirty years the ecological restoration of the Rhone has been achieved thanks to a proper consideration of the environment in the design and the operation of projets, including the increase of reserved flows, the restoration of old meanders and alluvial margins, the re-establishment of migration routes for fishes. The preservation of biodiversity for future generations along the Rhone and the societal utility of the river for the territories should be fully integrated in the pursuit of this development.

1. Why to develop a river?

Throughout history, the suroundings of the great rivers have always attracted people as a unique space for living, trading, farming and fishing.

The risks related to rivers include often devastating floods, erosion of banks and beds, severe droughts and obstacles to communications. Humans have braved these problems in order to enjoy the considerable wealth at their disposal: drinking water, fish production, quality of plains for agriculture, river transport routes, and – later – energy potential, water for industries, waste water treatment, source of building materials, water sports. Taken separately, each wealth can lead to conflicts over water use. Moreover, any significant change at any point in the valley can disturb the balance of the entire river dynamics and have far-reaching effects both in space and time (Read: Learning to live with rivers, a matter of geomorphology). From upstream to downstream, the river bed and the flood plain, as well as the surface runoff and the groudwater level are highly interdependent

The development of rivers through multi-purpose low head hydropower plans can contribute to an optimal use of their natural resources and ensure a balanced satisfaction of the different needs. Indeed, on lowland rivers, the development of low head on the stream dams, if well designed, do not alter water quality, do not modify sediment transport and contribute to the growth of navigation and rich agricultural plains. The services they can provide must be optimised to meet the objectives pursued, including energ

y production, navigation, agriculture, while ensuring that floods will not worsen.

However, the relative focus and priorities of these objectives change over time as new goals emerge such as tourism development, heritage restoration and increased awareness of environmental protection. Multi-purpose development of large rivers must demonstrate its capacity to adapt to these changes, including respect for the environment and even its restoration in the context of climate change.

The example of the development of the Rhone is presented, with the principle and evolution of this development over the last decades, and highlights the attention paid to a wide range of economic, social, environmental and sustainable objectives for the benefit of the territories.

2. Development of the Rhone

The French government, via the law of 27 May 1921, took the decision to develop the Rhone and assigned its management, for its French part [1], to the CNR (Compagnie Nationale du Rhone), created in 1933. Upstream of Lake Geneva, the Rhone is the property of the Federal Office for the Environment while downstream of the Lake, it is the property of the Canton of Geneva and managed by the Geneva Industrial Services (GIS). The management of sediment is organised in common between GIS and CNR, the latter also pursuing three main objectives:

- producing hydroelectric power

- providing a wide-gauge waterway

- promoting agricultural development.

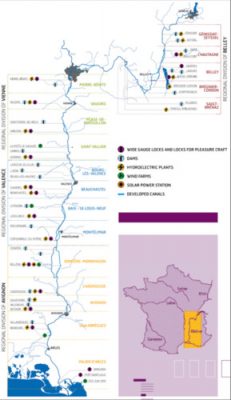

From 1948 to 1986, the CNR set up a cascade of 19 multipurpose plants [2] (3000 MW installed capacity) spread over 520 km between Switzerland and the Mediterranean Sea (Figure 1).

At present, the Rhone is a waterway in the European system. The river belongs to class Vb, i.e. according to the classification of the European Conference of Ministers of Transport, ECMT, it allows the navigation of boats with length between 172 and 185 m, width 11.4 m, draught varying between 2.5 m and 4.5 m and tonnage between 3 200 and 6 000 tonnes, between Lyon and the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, a surface area of 120,000 hectares has been managed to irrigation, the water needs of crops increasing from north to south: maize, rapeseed, early crops, orchards, rice (50% of the net withdrawals from the Rhone in 2014 [3]).

- a dam with movable gates that raises the level of the Rhone; equipped with fish migration facilities and a small hydroelectric power plant to turbine the ecological instream flow ;

- a diversion canal generally in the alluvial plain, with the hydroelectric power plant using the waterfall created by the dam, a navigation lock attached to the plant and water intakes for irrigation.

These works are completed, according to the needs imposed by the site, by

Dikes edged with counter-drainage channels protecting the riparian plains from the effects of impoundment. Flood expansion zones that existed prior to the developments are preserved to maintain flood-control capacity and to prevent the acceleration of floods downstream. These areas are fed by submersible dikes and spillways

- Industrial and port areas, marinas, etc.

- Other means of producing renewable energy (photovoltaic plants, wind turbines, etc.).

3. Changing objectives and priorities

Divergent interests in uses that largely influence development priorities and prospects are displayed by the diversity of stakeholders involved in the development of a major river.

The Rhone River, for example, although used during two thousand years as an axis of penetration and bordered by major cities and agricultural agglomerations, was still a wild river at the beginning of the 20th century, with untapped resources and devastating floods.

The main concerns of residents, whose initiatives were at the origin of the “Rhone Law” -1921, were therefore aimed at protecting them from bank instability, at insuring a stable supply of water for agriculture and at improving the navigation conditions of a river that could be too fast and with insufficient draft at low water levels.

The achievment of these objectives required major works and infrastructure; it was made possible withrevenues from hydroelectric development (one of the three objectives assigned to the CNR).

This model, based on hydropower as a means, navigation and agriculture as objectives, has largely dominated the conditions for achieving the development of the Rhone and constitutes its gene for the sustainable development of the Rhone Valley.

The good quality of surface and groundwater ressources linked to the Rhone is a central issue for all uses of the river: it was achieved through the implementation of European regulations toimprove the situation faced with historical pollution of industrial and agricultural origin,.

3.1. Power generation

- 250 times less carbon dioxide than coal-fired power plants,

- 3 times less than wind turbines,

- Four times less than nuclear power,

- 20 times less than photovoltaic solar power.

This is a long-term investment that contributes to the multi-purpose management of rivers.

Compared to other conventional sources of electricity, hydropower is a capital-intensive sector (creation of infrastructure and heavy equipment: figure 3) with high risks at the beginning of the project (hydrology, geology, social and environmental acceptance). Financial aspects can pose new challenges as energy assets often require short-term profitability.

The electricity market has been liberalised in France since the 2000s, allowing CNR to become an independent producer and to set up an innovative and integrated organisation to manage its intermittent energy production. Skills in forecasting, planning, marketing and remote control of its assets are being developed in order to optimize uncertainties related to price volatility and the risk of imbalance between production and sales (Figure 4).

In addition, CNR has diversified its sources of energy production with exclusively renewable energies, such as solar and wind power. It is also working on innovative technologies (tidal power, electricity storage and mobility, hydrogen storage, etc.) as part of the energy transition and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

This model adopted for more than 80 years continues to evolve and proposes a new relationship to energy through the convergence of public and private interests, economic efficiency and general interest. Since its creation, CNR has been a producer of green electricity and a developer of territories and intends to actively contribute to the energy transition in France and Europe.

After years of disinterest in this mode of transport, the French authorities have given the financial means to invest massively and sustainably a wide-gauge waterways, thanks to an original tax on multiple water uses. It has made it possible to reinvest in the equipment and infrastructure of major waterways, whose development lagged behind that of German waterways at the end of the 20th century.

Over the last decade, the French government has encouraged river navigation, including on the Rhone, considered as a truly sustainable mode of transport by aiming for an increase in non-road / non-air goods from 14% in 2009 to 25% in 2022 (Grenelle, planning law of 3 August 2009).

Sustainable inland waterway transport meets the requirements of the three principles of sustainable development :

- Environmental friendliness: river transport has both low energy consumption and low greenhouse gas emissions compared to road or air freight. On average, a convoy of tugboats on the Rhone, 4400 t – 264 TEU (TEU in English or EVP in French is a container measurement unit, here equivalent to Twenty Feet) avoids the use of 220 20-tonne trucks on the road.

- Economically competitive: Inland waterway transport can be up to four times cheaper than road transport for some supply chains. It involves a large number of sectors and is well integrated into international logistics networks (half of the tonnes/kilometers measured on the French national network have a European origin or destination).

- Socially acceptable: its social impact is positive, because it relieves congestion on the road network and because of the low number of accidents recorded. It has a strong development potential, particularly in the Rhone Valley, and generates multiple direct, indirect or induced jobs.

CNR has developed a network of 18 industrial and port sites to ensure the success of its mission as a concessionaire of the Rhone.

Their bridgehead is the Port of Lyon Edouard Herriot (PLEH), the largest port in the Rhone-Saône basin in terms of traffic and size. The network thus formed in the Rhone Valley is a major corridor linking the Mediterranean Sea, via the ports of Marseille-Fos / Sète, and the wide Saône River north of Lyon.

In addition, cruise ship traffic has increased rapidly in recent years, with 200,000 passengers on the Rhone in 2018.

3.3. Agriculture, irrigation and flood protection

The agricultural development of a country is an economic necessity and a matter of national sovereignty in many alluvial plains of the world.

The Rhone has benefited from the 32 pumping stations installed by CNR to promote irrigation, contributing to the development of more than 120,000 hectares of agricultural production.

Thanks to the financial support of agricultural policies (stabilization of water tables, soil consolidation, restructuration, market reorganization of agricultural products), the development of irrigation has made it possible to ensure the efficient development of the valley with the water supplied by the CNR pumping stations. It has improved yields thanks to agricultural inputs (fertilizers, pesticides).

It is recognized that this development was sometimes at the expense of natural wetlands adjacent to the river, and it took all the strength of nature protection associations to save some old arms of the Rhone and some particularly interesting natural areas.

At the same time, the value of flood expansion areas has been rediscovered, as well as their virtues, not only in maintaining land quality, but also in recharging groundwater and improving the ecological quality of wetlands. In addition to its mission to irrigate the valley, CNR is committed to provide its know-how and expertise, and to support research and experimentation, particularly in terms of adaptation of agricultural techniques to reduce the consumption of water and phytosanitary products and to preserve biodiversity.

3.4. Other industrial uses

In the Rhone Valley, the industry has still a greater weight in the local economy than in the French average. The industrial activity is multiple and is mainly located downstream from Lyon. It concentrates nuclear, chemical, petrochemical and pharmaceutical companies. It accounts for 36% of the annual net withdrawals from the Rhone basin (Ref 5). A major constraint concerns the cooling of the nuclear power plants located along the Rhone (21% of the annual net withdrawals), both in terms of flow and temperature: note the recent appearance of periods of stress, particularly during heat waves and/or pronounced low water levels (particularly in 2003 and 2006).

3.5. Aquatic leisure and river tourism

Today, these water uses are taken into account from the very beginning of project development, at the initiative of local authorities in consultation with the project owner. This early awareness generates savings for leisure facilities, taking advantages of the presence of site machinery, availability of materials, etc.

Along the Rhone, several marinas with 200 to 300 berths, numerous water sports facilities and more complete developments including a port, beach, swimming pool, white water stadium, fishing grounds, holiday village, restaurants and adapted shops have been created.

The development of the Rhone waterway has enabled the development of collective and individual river tourism. On the Upper Rhone, new leisure locks were introduced a few years ago to allow wider access for pleasure boats on the Rhone. These facilities were built as part of the Missions of General Interest programme.

3.6. Adaptations to climate change

The studies conducted on climate change [6] predict variations in the flow amplitudes of the Rhone by the end of the 21st century, with a winter increase (due to a temporal shift in snowmelt) and a sharp decrease periods -50 to 75% depending on the climate scenario- during low-water due to the gradual disappearance of glaciers. This change is likely to create conflicts of use in the summer period: in particular, with regard to irrigated agriculture in the South of France and to the cooling of the nuclear power plants operated by EDF along the Rhone.

4. Missions of general interest (MIGs) and adaptation to the environment

4.1. Ecological flows

The increase in ecological flows in the Old Rhone (the natural stretches bypassed by the developments) is very instructive in this respect. The value of instream flows has changed over time and with the way society takes the environment into account.

Ecological flow varied by development, physical criteria (length of the canal, whether it was fed by a tributary or not …) and by season (lower in winter, higher in summer, sometimes an additional intermediate season was considered).

On the Bas-Rhone, instream flows were relatively low compared to the average river flow: several tens of m3/s on average for modules between 1000 and 1700 m3/s. These flows prevailed even after the publication of the “Fishing” law of 1984, establishing minimum values for the reserved flows but excluding the Rhone and the Rhine from its scope of application due to their international status.

The Water Development and Management Master Plan (SDAGE) established in 1996, then the 10-year hydraulic and ecological restoration plan for the Rhone initiated in 1998 by the State, followed by a modification of the CNR specifications in 2003, identify several sections of the Rhone in which the increase in the reserved flow could be put into practice with the aim of restoring it as a “living and flowing” river.

It is in this context, and supported by the local demand of the Rhone riverside residents, that the ecological flows of the Rhone have been progressively increased with the installation of small hydropower plants (SHP) at existing dams, as well as the installation of fish passes.

The ecological interest of several sectors of the Rhone has thus been well taken into account to reduce the risk of eutrophication

4.2. Restoration of migration routes for migratory fish

In 1992, the first phase of the “migration programme” in the Rhone basin provided for the extension of the shad distribution area to spawning grounds located on the main tributaries of the right bank of the Rhone, as it was the case in 1952. Thus, an original technical solution was proposed to re-establish the migration blocked downstream of the river by the first obstacle of the Beaucaire hydroelectric plant using the navigation locks. Other reasons for choosing this solution included the amount of the investment, which was on the order of 10 to 20 times less than the cost of establishing a specific system.

Today, the question is how to specify a new target for shads and how to take into consideration other species, such as eels, which have been the subject of a national and local management plan since 2009.

Thus, in the medium term, a strategy has been set up within the framework of the Rhone Plan with the following objectives:

- continuing the recolonisation of the Rhone basin by shad upstream from the Drôme,

- improve eel spawning tracks by promoting the installation of specific passes,

- not to jeopardise the downstream migration of eels by installing suitable migration systems at small hydroelectric power stations.

All these measures should be completed in the next few years.

4.3. Wetland conservation, restoration of meanders and alluvial fringes

In the context of the construction of the last works on the Upper Rhone (late 1970s to early 1980s), this evolution is clear, the recognition of the river’s natural heritage has been acquired and the will to preserve it has been clearly demonstrated.

These years ushered in and foreshadowed a new era of ecological restoration projects that began in the 1990s and became widespread in 1998. Ecological objectives had to remain compatible with the concessionaire’s obligations. The strategy was to achieve objectives and not to oppose them, allowing for rapid progress. The association of different partners (water agency, associations, scientists…) reinforced this development of mentalities and the type of progress made.

Improvements in biodiversity and habitat conditions therefore depended on a combination of measures: increasing instream flows with restoration of “lônes”. The knowledge gained from these projects then led to the consideration of action with regard to alluvial margins. Since 2003, most of the restoration work has been developed through the environmental component of the CNR’s Missions of General Interest, which are also added to the Rhone Plan.

5. A Lesson for Future Multi-purpose Developments

Imagined and designed with economic objectives that reflected their times, the multi-purpose developments on the Rhone had to be able to adapt continuously to changes in these objectives and their respective priorities.

This necessary adaptation has been a powerful factor in economic and technological progress in many areas. Since thirty years, another priority was to take into account the environment in the design and operation of projects, a problem initially neglected by decision-makers.

The multi-purpose developments were able to demonstrate their adaptability and ability to meet the challenges of the Rhodanian territories. This concept related to multipurpose facilities has made several advances, including two main ones:

- It has led to significant progress in our knowledge of the major river networks (dikes, dams, turbines, locks, irrigation, integration in valleys) in France and around the world. This progress has also concerned the natural environment through knowledge of the functioning of river hydrosystems in all its biotic (plant and animal species) and abiotic (physical environment) components during the work of scientists.

- It has demonstrated, thanks to innovative designs and efforts invested in supervision during construction and then in operation of the structures, the robustness of the facilities (including during floods) for more than half a century with regard to its three founding missions. In terms of the environment, the impacts have continued in the continuity of those already begun since the first correction of the Rhone at the end of the 19th century to promote navigation.

There is no doubt that the landscape and river environment of the valleys have been greatly modified by man over the course of development. However, the river continues to live and bring wealth to the territories it crosses. It has been and must continue to be a vector for economic development. Concerning the environment, major restoration programmes have been undertaken over the last 20 years: re-watering of the river annexes, reactivation of the lateral dynamics, sediment continuity, increase in reserved flows, improvement of the piscicultural continuity on existing and especially new obstacles. At the global level, this work has become a technical and scientific reference (state of knowledge, design, benefit assessments).

In a context of an energy transition that is imperative for our civilisation in order to combat global warming, its three founding missions make even more sense today. They still need to be developed and reinvented: production of renewable and non-carbon energies (optimization, wind power, photovoltaic…), transport of goods, support for the transformation of an agriculture that is increasingly concerned by the environmental challenges of the 21st century (management of water resources). To these, the preservation of biodiversity for future generations along the Rhone and the river’s societal usefulness for the territories deserve to be fully integrated in the pursuit of this development.

Notes and References

Cover image. [Source: © Camille Moirenc]

[1] For cross-border management: PFLIEGER, G, BRETHAUT, C. GOUVRHONE: Cross-border governance of the Rhone, from Lake Geneva to Lyon. 2015 https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:78922

[2] For details of the facilities

[4] See the video on the Génissiat dam

[5] See IPCC (2012), Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation. Special Report, Cambridge University Press.

[6] BENISTON M. (2019) – The impact of climate change on Alpine snow cover and glaciers: consequences on water resources, Encyclopedia of the Environment, [online ISSN 2555-0950]

[7] NEMERY J. (2019), Phosphorus and Eutrophication, Encyclopedia of the Environment, [online ISSN 2555-0950]

The Encyclopedia of the Environment by the Association des Encyclopédies de l'Environnement et de l'Énergie (www.a3e.fr), contractually linked to the University of Grenoble Alpes and Grenoble INP, and sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences.

To cite this article: JOUVE Daniel, MOIROUD Chritsophe (January 5, 2025), Multi-purpose river development: example of the Rhone River, Encyclopedia of the Environment, Accessed March 14, 2025 [online ISSN 2555-0950] url : https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/water/multi-purpose-river-development-example-rhone-river-2/.

The articles in the Encyclopedia of the Environment are made available under the terms of the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which authorizes reproduction subject to: citing the source, not making commercial use of them, sharing identical initial conditions, reproducing at each reuse or distribution the mention of this Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.