为什么要处理城市污水?如何处理?

在世界人口持续增长和城市化进程加快的背景下,提供饮用水和卫生设施仍然是许多城市,特别是发展中国家的城市一个至关重要的问题。卫生设施是指在废水能够排放到自然环境之前,用于收集、运输和处理废水的所有技术的总称。它可以按照城市区域规模进行规划设计(即集中式卫生设施),也可以按住宅居所规模进行构想,也即不连接到集中式下水道网络(即独立式卫生设施)。未来的污水处理厂倾向于成为真正的污水处理厂,在那里可以产生绿色能源、肥料和贵金属,并重复利用处理后的污水。

1. 城市卫生简史

最早的排水系统建于古代,如古罗马著名的马克西马下水道(图1)。罗马帝国灭亡后,排水系统逐渐被废弃。污水、粪便和其他废弃物被直接排放,造成恶臭、井水污染和许多疾病。

在19世纪接踵而至的霍乱疫情席卷全球之后,19世纪50年代的卫生改革运动提倡建造地下排水系统(图2),将生活污水、雨水和街道水直接排入河流或海洋。因此,巴黎市污水管网的长度从1853年的150公里增加到1890年的近900公里(目前约2500公里)。1894年颁布实施的一项法律强制要求巴黎的建筑物将其废弃物、雨水以及黑水[1]排入新建设的(所谓的合流制)排水系统[2]。污水系统的概念就这样出现了。

直到20世纪60年代,新城区和新城市才开始建设分流制排水系统,分别收集和处理生活污水和雨水。污染性工业活动产生的废水不能直接排入污水系统,必须由工业部门自行处理。鉴于污染物性质和处理工艺的多样性和特殊性,本文将不讨论工业废水的情况。

污水排放将污染问题转移到城市之外,对地表水造成越来越严重的污染。最早的污水净化技术出现在19世纪60年代,将污水喷洒在沙质土壤之上,以利用土壤的净化能力,同时增加农业和商品蔬菜种植业产量。

伴随着城市化进程的不断加快和污水收集量的不断增加,用于污水净化的土地面积也在增加(1900年左右,在巴黎高达5000公顷)。在1870年至1900年间,污水净化容量也在缓慢增加,这得益于在污水喷洒之前通过沉淀、化学处理或厌氧发酵(即在无氧情况下)的方式去除其中的固体物质。

19世纪80年代,出现了由焦炭、底灰、火山灰等材料制成的高孔隙率人工滤池,促进了生物膜[3]净化反应器(生物滤池)的巨大发展。这些反应器是细菌的温床。第一座生物膜净化反应器于1893年建于索尔福德(英国)。

1914年,英国研究人员阿登和洛克特发现,在待处理的污水中投加已经形成的净化生物,污染控制要快得多[4]。他们由此申请了净化工艺的第一个专利,被称为活性污泥法。该工艺不使用滤池,而是基于极大程度地培养悬浮在水中的净化生物(活性污泥)。该工艺于1914年在英国以单反应器(序批式进水)的形式首次实现了工程应用,随后在1916年以连续进水生物反应器并与沉淀池(或澄清池)相连的流程形式实现了工程应用。

得益于机电设备的进步以及自20世纪70年代以来在认识和优化消除氮和磷污染(脱氮除磷)反应方面的科学知识积累,这些工艺到今天还一直在不断地改进。虽然早在20世纪20年代和60年代就已经建成了许多生物滤池和活性污泥工艺污水厂,但直到20世纪70年代,发达国家的污水处理厂建设才真正开始加速,这得益于人们日益增强的保护环境的集体意识以及日益严格的法规条文(阅读《法国水法》)的支持。

2. 为什么要处理城市污水?

2.1 城市污水组成

城市污水中含有大量的有机和无机化合物,这些化合物来源于黑水(含有尿液和粪便)、从厨房、洗衣房和浴室排出的脏水以及地表径流。为便于分析和监管,通常使用包括多种污染物的综合指标(以毫克/升表示)来表征未经处理和处理过的废水:

- 悬浮物(SM)的含量,它代表能被2µm孔径滤膜所截留的颗粒物污染。它们由大约25%的矿物质和75%的被称为挥发性物质的有机物组成。挥发性悬浮固体是COD的重要组成部分。

- 化学需氧量(COD)是完全氧化其中的溶解性和颗粒态有机污染所需的氧气量,包括可生物降解COD和不可生物降解COD两部分。这种完全氧化是在非常酸性的环境中通过使用非常强的氧化剂(重铬酸钾),并且在约150°C的温度下反应2小时完成的[5]。对于未经处理的生活污水,约50%的COD为溶解态,另50%为颗粒态。

- 五日生化需氧量(BOD5)是指细菌在5天内降解其中的可生物降解有机物时所消耗的氧气量。城市污水的COD/BOD5比值较高(2 ~5),这表明有机污染物可以很容易地在污水处理厂中被生物去除。

- 凯氏氮[6](NK)是有机氮(包括尿素、氨基酸、蛋白质……)和氨氮(N-NH3)的总和。

- 总氮(NGL)指的是有机氮、氨氮、亚硝态氮以及硝态氮的总和。后两种形式的氮都不存在于未经处理的城市污水中。

- 总磷(Pt)包括有机磷和无机磷。

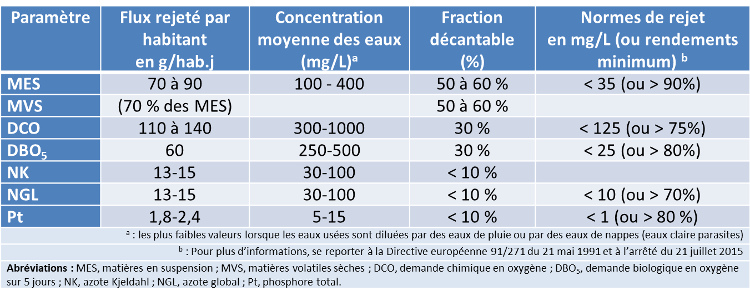

表1给出了污水处理厂入口处城市污水的平均水质特征以及法规要求的已处理污水的最低水质要求(最高允许浓度或最低处理效率)。

表1. 未经处理的城市污水的平均组分和大型污水处理厂的排放标准示例(超过10万名居民)。

les plus faibles valeurs lorsque les eaux uses sont dilues par des eaux de pluie ou par des eaux de nappes (eaux claire parasites) 用雨水或地下水(寄生清水)稀释使用过的水时的最低,Pour plus d“informations, se reporter a la Directive europeenne 91/271 du 21 mai 1991 et larrete du 21 jillet 2015 有关更多信息,请参见1991年5月21日的欧洲指令91/271和2015年7月21日的指令,

Abréviations : MES, matiéres en suspension ; MVS, matiéres volatiles sèches ; DcO, demande chimique en oxygène ; DBOs, demande biologique en oxygènesur 5 jours ; NK, azote Kjeldahl ; NGL, azote global ; Pt, phosphore total.缩写:MES,悬浮物;MVS,干挥发性物质;COD,化学需氧量;BOD5,五日生化需氧量;NK,凯氏氮;Pt,总磷。]

城市污水中还含有许多浓度很低(从几ng/l到几µg/l)的无机和有机化合物。微污染物质的主要种类有化妆品、农药及杀虫剂残留、溶剂、天然及合成激素、药物残留、金属等。这种微污染是对环境排放有害物质进行管制行动运动的主题。目前,人们特别关注污水处理厂进水和出水中农药残留、药物和内分泌干扰物的浓度水平。

城市污水还含有高浓度的粪便微生物,特别是病原微生物,其数量和类型取决于人口的健康状况。

2.2 排放对水环境的影响

未经处理的城市污水排放到地表水中会造成视觉污染(漂浮物),降低水的透明度,并造成湖泊和河流的淤积。可生物降解物质的排放会增强水体中的微生物活性,从而导致溶解氧浓度降低,甚至导致水体中其他生物因缺氧而窒息死亡。氮和磷的排放会导致水体富营养化现象(阅读《磷与富营养化》和《环境中的硝酸盐》)。

微污染物的排放会对水环境中的动植物产生毒性作用。这些影响包括食物链中持久性分子的生物累积、极低剂量导致的慢性毒性以及内分泌系统功能的变化,这些影响可能导致诸如雄性鱼类雌性化等后果。水的微生物污染会使水质不适合某些用途。

2.3. 废水处理义务

自然存在于地表水中的微生物能够降解污水排放带来的污染物质,但河流的自净能力普遍非常不足。因此,污水在排入自然环境之前必须在处理厂进行处理。关于各种综合污染指标,已处理污水不得超过的其最大允许浓度值或应达到由法规条文规定的最低净化效率,见表1(另见《法国水法》)。

3. 废水如何处理?

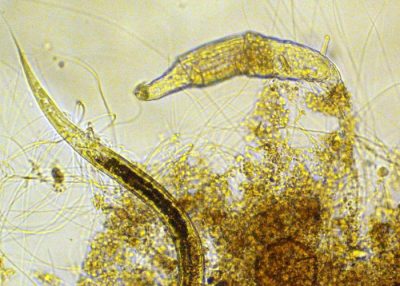

城市污水主要采用生物法进行处理,并与液/固分离工艺(沉淀、过滤、气浮)相结合,以去除悬浮固体和保留产生的生物物质。起净化作用的生物物质基本上由细菌(初级生产者)组成,这些细菌具有分泌胞外多聚物[7]的特性,可以形成可沉降的絮体[8]或生物膜,在这些絮体或生物膜中,其他微生物(原生动物、后生动物)作为掠食者也不断繁殖(图3)。

生物去除有机物、氮和磷污染的反应都需要特别的运行条件(溶解氧的存在与否、生物质在反应器中的停留时间等)。这些污染物的去除或者水的净化是通过悬浮在水中或附着在填料上的生物物质的培养来完成的。

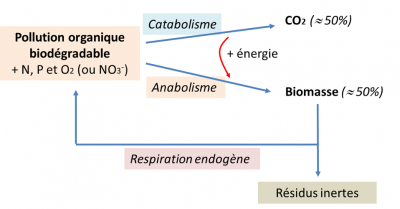

3.1. 污染的生物转化

可生物降解的有机物(由蛋白质、脂肪和碳水化合物组成)被称之为异养细菌的微生物用作食物,因为它们利用有机碳作为其发育和繁殖(合成代谢)的碳源以及能量需求(分解代谢)的来源(图4)。产生新细胞还需要氨氮和磷酸盐的参与,它们在未经处理的污水中的浓度能大大满足需求。在溶解氧或硝酸盐存在的情况下,污水中的有机物大致以相同比例转化为二氧化碳和生物物质(图4)。

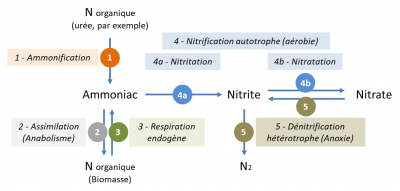

氮污染在污水处理厂的主要转化反应为氨化、同化、硝化和反硝化(图5):

- 氨化作用(反应1)将有机氮(主要包含在污水尿素中)转化为氨氮。这个反应很快;许多种类的微生物可以完成此反应:

尿素[CO(NH2)2]→氨[NH3]+二氧化碳[CO2]

- 同化作用(反应2)是指氨氮被细菌同化形成新的有机氮生物分子用于合成新的细菌。

- 生物硝化作用(反应4a和4b)通过氨氧化菌将氨氮(铵,NH4+)转化为亚硝酸氮(亚硝酸盐,NO2–),然后通过硝化细菌将其转化为硝态氮(硝酸盐,NO3–):

铵[NH4+]→亚硝酸盐[NO2–]→硝酸盐[NO3–]

这些反应只在有氧的条件下才能发生,是由被称之为自养细菌的微生物完成的,因为它们利用无机碳(CO2或HCO3–)作为碳源来合成新的细菌。

- 生物反硝化(反应5)将硝酸根离子(NO3– )还原为氮气(N2)。在污水处理厂,反硝化只有在无氧条件下才能发生。反硝化由异养细菌完成,需要消耗有机物。以甲醇(一种易生物降解的有机小分子)作为反硝化过程的有机物为例,反硝化伴随着有机污染的消除(被氧化成CO2):

硝酸盐[NO3–]+甲醇[CH3OH]→氮气[N2]+水[H2O]+二氧化碳[CO2]

与氨氮的去除一样,硝化过程生物量的增长伴随着通过同化作用部分去除磷(将磷合成至新的生物分子)。

为了进一步生物除磷,需要将生物物质交替经历厌氧和好氧阶段,从而形成被称之为聚磷菌的除磷细菌,这类细菌具有在其细胞中过量聚集磷的性质。磷可占除磷细菌干重的10%-12%,而磷在非除磷细菌干重中的比例为1%-2%。

在污水处理厂中,生物除磷仅去除约40%-60%的磷。为了达到排放标准(见表1),还需辅以物理化学除磷,即采用添加铁盐(通常为氯化铁,FeCl3)的方法通过形成磷酸铁沉淀去除。

3.2. 大型污水处理厂使用的集约型工艺

当能集中收集到超过2000-4000 人口当量的污水时 [9],一般在集中式污水处理厂进行,其中用于污水净化的微生物要么悬浮在水中(称为活性污泥),要么固定在填料上(浸没式生物滤池)。这些污水处理厂的优点是占地面积小。然而,这些处理厂会消耗大量能源(约60-90千瓦时/人/年),特别是通过搅拌和曝气的方式向细菌提供氧气(图6)。这些处理厂会产生大量的剩余污泥(20-22千克干物质/居民/年),主要由不可生物降解的悬浮物和在生物反应器中产生的生物物质组成。

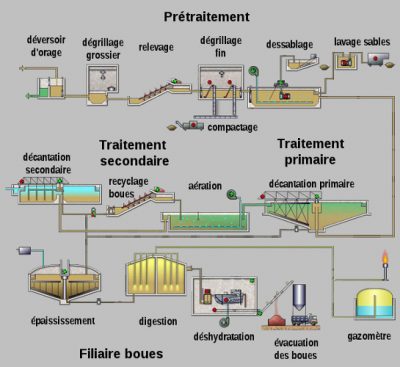

一座活性污泥法污水处理厂(图7)包括:

- 预处理步骤,以去除大碎屑(格栅单元)、砂(除砂单元)和油脂(脱脂单元)

- 活性污泥反应器

- 沉淀池(称为澄清池)

- 在排放到自然环境之前,还可能包括三级处理(如紫外线照射消毒)。

活性污泥法污水处理厂通常包括两个或三个串联的生物反应器,其布局和操作条件的选择是为了优化有机物、氮和磷污染的去除效率。在澄清池中,在活性污泥池形成的细菌絮体发生液/固分离,即经过处理的污水从澄清池上部溢流出水,而污泥则在澄清池底部的沉淀(图8)。部分污泥返回到生物反应器中,剩余污泥则被送至污泥处理和资源/能源回收系统。这种类型的污水处理厂于1914年发明,目前用于处理法国90%的城市污水。

用多孔膜过滤代替澄清池可以在生物反应器(膜生物反应器)中实现更高的生物量浓度。与沉淀法相比,膜过滤可确保处理后的水中不含悬浮固体,并能更好地去除细菌[10]。

生物过滤法污水净化厂。这一工艺在20世纪80年代开发,通过在浸没式滤池中形成的附着生长生物物质去除有机物污染和氮污染。滤池中的介质(粒径:4-6 mm)既是生物膜生长的填料,也是过滤介质。在生物滤池出口处,经处理后的水可直接排放到接收水体环境中(无需澄清池)。为了避免生物滤池被过快堵塞,在生物过滤前要彻底去除污水中的悬浮固体。每天对生物滤池进行清洗,可以将过滤过程中截留的悬浮物和产生的生物量清除出滤池。

3.3. 小型污水处理厂使用的粗放型工艺

小型社区(小于1000-2000 人口当量)产生的污水通常通过天然泻湖法或种植了芦苇的滤池进行处理。这些广泛的净化工艺(也称为乡村工艺)不需要任何预处理(通过格栅去除大于10-15 mm的杂物除外),不需要机电设备,也没有任何电力消耗(泵送除外)。

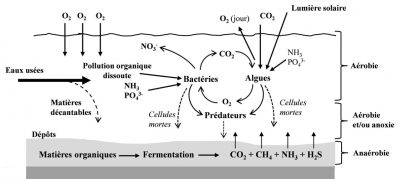

天然泻湖法是指将待处理污水在3个串联起来的、池深较浅(1-1.4 m)的、不渗漏的水池(泻湖)中循环处理数十天(图9)。

天然泻湖法污水处理主要是通过发生在上层水层的生物反应以及发生在池底的可沉降物质的沉淀而实现的(图10)。

- 上层水层:在耗氧条件下,细菌氧化降解可生物降解有机物(特别是在第一个水池中)和含氮有机物(硝化作用主要发生在第二和第三个水池中)。溶解氧是通过水和大气间的交换提供的,其中微藻(光合作用)起重要作用。在生长繁殖过程中,微藻同化吸收了污水中的部分氮和磷。

- 池底:由于泻湖底部没有溶解氧(没有光合作用),可以发生硝态氮的部分反硝化以及可能导致厌氧发酵反应(产生硫化氢)。

泻湖法的污水净化性能随季节的变化而变化,随日照和水温的变化而变化。由于沉淀物的淤积,池子每10至12年需要清理一次。

芦苇滤池代表了天然沼泽的人工版本(图11)。常规的方法是通过两个串联起来的滤池过滤大颗粒杂质已被事先清除(经格栅)的污水。每个滤池由种植了芦苇的、厚60至90厘米的砾石层组成。生物净化是通过将悬浮固体截留在滤池表面以及通过附着在滤料和芦苇根系上的起净化作用的生物量来实现的。芦苇的基本作用是在风的作用下实现对滤池进行机械清洁。种植芦苇的滤池所需的占地面积比天然泻湖法小5到6倍,并与周围的景观非常契合(见重点:芦苇滤池)。

4. 未来的污水处理厂:真正的能源和资源回收工厂

污水处理厂的主要目标是减少排入自然环境中的污染物的量。它们也可以成为真正的工厂来生产绿色能源、原材料或回用处理后的水[11]、[12]。这些新功能是城市和地方当局制定的可持续发展、循环经济、可再生能源生产和全球变暖倡议的一部分。

4.1. 绿色能源生产

每个居民每年产生的污水对应在污水厂产生约20至25千克(干重)的污泥。这种污泥含有约65%的有机质、氮和磷,长期以来一直用于农业(施肥、堆肥)。目前它们越来越多地在大型污水处理厂用于生产可再生能源。污泥焚烧(单独或与生活垃圾一起焚烧,或在水泥厂使用)减少了化石燃料的消耗。

每人每年产生的污水厂污泥的厌氧消化可产生约6 m3的沼气(含有65%的甲烷和30%的二氧化碳)。沼气经净化后可用于供热或发电,或注入城市燃气管网。污水厂污泥的甲烷化是一个成熟的工艺,目前正在建设新装置以寻求提高沼气产率和回收率的方法。

如果有足够的水头和水量,可以在污水处理厂的上游或下游管道中安装涡轮机,将水能转化为电能。由此,瑞士可以通过经济有效的方式从污水水头中获取至少9.3 GWh/年的水力发电量,目前已经实现了3.5 GWh/年的产能[13]。

污水热能[14]是一种可再生能源[15]。可以利用热交换器从污水管网或污水处理厂回收热能,以供热泵产热和致冷。目前,污水热回收正在经历一个非常快的发展阶段,用于公共建筑、游泳池和其它建筑物的生活热水生产、供暖和空调方面。目前正在开展中试研究,以利用处理后污水中的氮和磷作为营养源种植微藻作物,从而生产生物燃料(阅读《生物燃料:是否是微藻的未来?》)。

生物桩是一类反应器,利用细菌直接将在氧化可生物降解化合物过程中释放的能量转化为电能。目前的研究热点之一是开发出在技术上和经济上都可行的生物桩。

4.2. 原材料生产/资源回收

磷可以从污水中沉淀下来(以磷酸钙或鸟粪石颗粒的形式[16]),并用作农业肥料。首批磷回收工业项目之一(丹麦奥胡斯污水处理厂,85,000 人口当量)的结果表明,每个居民每年排放700-750g磷,其中有60%可以被回收,从而减少了磷酸盐矿石的进口量。

污水中含有铜、银、金、铂、钯、钒等贵金属和稀有金属,根据美国亚利桑那州立大学的研究结果,一座100万人口的城市,其每年产生的污水厂污泥中含有价值1300万美元的金属,其中含有包括260万美元的金和银。这些金属存在于污水厂污泥中[17]。在日本,有一家污水处理厂已经开始从污水厂污泥的焚烧灰中回收黄金[18]。

最近的小试研究表明,有望能够利用细菌转化污水或污水厂污泥中的有机物生产可生物降解的生物塑料(聚羟基烷酸酯:PHA)。一个处理规模为100万人口当量的污水处理厂具有每年生产18,000吨PHA的潜力。

4.3. 再生污水回用

世界上许多地方都面临着季节性甚至长年缺水问题,而经过处理的污水可以重新利用,以弥补水资源的不足。它们可用于浇灌绿地和高尔夫球场、灌溉农业区、满足工业用水需求或生产饮用水[19](直接用于饮用水的生产,或通过向水库补水或向地下水体下渗的方式间接用于饮用水的生产)。根据污水的回用目的不同,污水经处理厂处理后需经过适当的后处理,程度从简单的消毒到远远复杂的系列处理不等。

5. 需要记住的信息

- 起初污水处理的目的是用于大型城市的卫生和居民健康保障,而后在20世纪70年代起开始扩大到满足更严格的排放标准以保护自然环境。

- 城市污水采用生物法处理,辅以物理化学法除磷。工业废水在特定的装置设备中单独处理。

- 在居住人口超过2000至4000人的城市地区,集约型污水处理厂主要采用活性污泥法(在法国有90%的城市污水被收集处理)。

- 对于小型社区,粗放型污水处理厂使用天然泻湖法或芦苇滤池。

- 关于污水厂的技术开发正在不断进行中,目前集中在污水厂污泥的利用,包括以沼气或热能的形式回收能量,以及生产肥料或生物塑料,有时还回收提取其中的金属。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:Antwerp-Zuid废水处理厂。[来源:作者:Annabel[CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)],来自维基共享资源。]

[1] 来自厕所的粪水。

[2] Tabuchi J.P.(2008)巴黎城市污水处理,南特,塞纳河-诺曼底水务局, 35页http://www.reseauprojection.org/ateliers/niamey_2009/Documents_annexes/session%203%20-%20Histoire%20assainissement%20agglo.%20parisienne%20JPT.pdf

[3] 生物膜是微生物(细菌、真菌、藻类或原生动物)的群落,它们相互粘连,并粘附在一个表面上,以分泌一种粘性和保护性基质为标志。它通常在水中或水中过滤介质中形成。

[4] 活性污泥中的净化功能生物物质是由活的或死的微生物(细菌和放线菌)、有机物和/或矿物碎片、胶体和由小动物组成的微动物群的混合物组成的,群落与地点有关。

[5] 例如,植物残渣(颗粒污染)在酸性介质中被重铬酸钾氧化成二氧化碳,因此消耗氧气(消耗1摩尔重铬酸钾=消耗 1. 5摩尔氧气)。

[6] 凯氏方法是1883年由丹麦人Kjeldahl开发的一种测定样品中氮含量的技术。后来经过大幅度修改,它被称为Kjeldahl, Wilforth and Gunning测氮法。

[7] 微生物排泄的分子,会发生聚集,例如在生物膜中。

[8] 污水中含有很大一部分由胶体组成的有机物,这些胶体由于带有负电荷而无法聚集。为了破坏这种悬浮液的稳定性并回收化合物,有必要通过减少胶体的静电排斥力来促进胶体的聚结,这就是混凝阶段。微小的絮状物相互聚集,形成更大的片状物,直到它们在重力作用下变得可以沉降,絮体就这样形成了。

[9] PE=人口当量。用于评估污水厂处理能力的计量单位,基于每人每天排放的污染量,相当于每天60克BOD5。(例如,一个1000人口当量的处理厂每天接收60公斤BOD5)

[10] 细菌的减少对应于污水处理后环境中细菌数量的减少。

[11] Found E. (2010) 未来的污水处理厂《科学编年史》17期13 页。

[12] ARMC,罗纳-地中海科西嘉水务局(2016)。未来的污水处理厂–她足智多谋!(5页的小册子)。

[13] Bousquet C., Samora I., Manso P., Schleiss A., Luca Rossi L., Heller P.(2015)。污水涡轮发电–瑞士的潜力如何? Aqua and Gas(水和天然气),15,54-61。

[14] 污水的温度在12℃至20℃之间,与测定时间和季节有关。

[15] De Batz S., Van den Bossche H. (2007).通过污水净化系统生产可再生能源–一些例子。 Techniques Sciences and Methods(技术科学和方法),12,67-83。

[17] Westerhoff P., Lee S., Yang Y., Gordon G.W., Hristovski K., Halden R.U., Herckes P.(2015)。美国全国各地污水处理厂的市政污泥中金属的特征、回收潜力和价值评估。Environmental Science & Technology(环境科学与技术),49(16),9 479-9488。

[18] 长野(日本中部)附近的诹访市的一个污水处理设施,每吨污泥焚烧灰中可回收1,890克黄金。焚烧灰中黄金的重量比很高可能是由于该地区有大量的精密设备制造商。这个黄金含量比金矿的含量高得多。例如,日本的Hishikari矿(住友金属矿业有限公司)每吨矿石的贵金属含量为20至40克。

[19] J. Haarhoff, B. Van der Merwe (1996) 纳米比亚温得和克污水再生的25年,Water Science and Technology(水科学与技术) 33 (10-11) 25-35。

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: DE LAAT Joseph (2024年3月9日), 为什么要处理城市污水?如何处理?, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年4月24日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/eau-zh/why-how-treat-urban-wastewater/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。