香料和香草:对我们的健康有什么好处?

烹饪中添加香料和香草可以增加进食的愉悦感,同时也能带来丰富的营养,有助于人体健康。产生香料和香草独特风味或刺激性气味的化合物往往参与植物的防御,以免其受环境破坏。 添加到食物中的香料和香草在被人体摄入后,仍然能在很大程度上保持生物活性:例如,它们的抗氧化特性对人体健康有益。香料和香草可以降低“文明病”的风险,例如肥胖、 而且近期研究证实香料和香草还可以促进人体微生物群中“有益”菌的生长。此外,由于强烈的芳香和风味 ,香料能够减少烹饪中脂肪、盐和糖的含量。

1. 香草和香料的发现

1.1. 香料与文明

“香料”一词来源于拉丁语中的“物种”,而“物种”又来源于“杂货商”,即香料的销售商 。在西方人的眼中,香料起源于象征着奢华的遥远国度,或者更确切地说象征着“用现金支付”,象征着精致。几个世纪以来, 为了垄断香料贸易,斗争和暴力源源不断。香料的历史就是一部文明史[1]。早在6000 多年前的北欧,就已发现了香料的使用。 随后 ,在美索不达米亚和古埃及,香料因其色香味独到,亦或具备食物保存的能力而备受人们喜爱 。随着大希腊地区的贸易增长和罗马帝国的扩张 ,香料又被带到了欧洲(阅读焦点——香料之路,全球化的第一批果实 )。

中世纪以来,在欧洲,香草的药用价值就已广为人知。但直到20世纪,香料的使用本质上仍然是享乐主义的(气味和芳香)(图 1)。

1.2 香草,香料–公共健康感兴趣的话题

直到最近,才有科学研究报道 香草和香料对公共健康具有潜在的益处。其集中体现在三个领域:

- 香料和香草中生物活性化合物的分析与鉴定;

- 在遵循公共卫生高级委员会(HCSP)营养建议方面,香料和香草的实际行为效用[2]:减少盐、脂肪与糖,增加蔬菜与豆类的摄入;

- 生物和临床研究证实,香料和香草有预防或缓解 疾病的能力。

1.3 什么是香料?什么是香草?

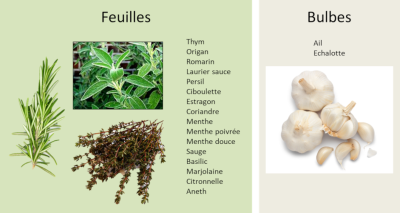

叶类:thym百里香、origan牛至、romarin迷迭香、laurier sauce豆豉、persil香芹、ciboulette小葱、estragon香菜、menthe薄荷、menthe poivree薄荷、menthe douce甜薄荷、sauge鼠尾草、basilic罗勒、marjolaine马郁兰、citronnelle柠檬草、aneth莳萝

球茎类:ail大蒜、echalotte葱

香料和香草都来源于植物[3]。通常,香料(英语国家所言的香料 )来自于植物不含叶绿素的部分,而香草是使用植物绿色的部分,以此来区分两者。

香草经常出现在菜园或菜市场的摊位上,基于其芳香 、调味或药用的品质,有时混合在芳香混合物中 (图2)。它们的活性成分存在于叶子(欧芹、月桂叶、 …)或鳞茎(大蒜、葱 、洋葱)中。在烹饪中,香料包用来给炖菜调味。香料包由各种香草组成,通常含有月桂叶、百里香和欧芹。

Safran番红花fleurs花朵clou de girofle丁香 bourgeons芽 cannelle肉桂 ecorces皮 gingembre生姜 curcuma姜黄 reglisse甘草 racines fruit果实 poivre piment paprika coriander genievre vanilla Graines种子 cumin孜然 noix de坚果 muscade肉豆蔻 fenouil 茴香celery芹菜 fenugrec胡芦巴 cardamone豆蔻 moutarde芥末

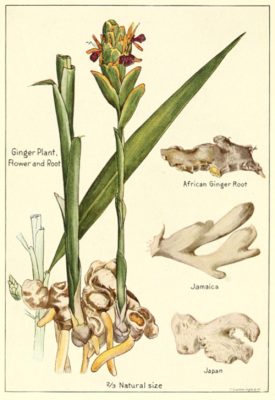

烹饪中香料的用量很少,主要用于给菜肴增香和调味,有时也用于上色或保藏。在香料中,生物活性物质可能存在于植物的花(藏红花)、芽(丁香)、树皮(肉桂)、根、果实(胡椒、莳萝、芥菜)、根茎(姜)或种子(茴香、香菜、肉豆蔻)(图3)。

香料之所以能刺激我们的感官,不仅是因为它们含有芳香或刺激性的化合物,更重要的是它们具有刺激三叉神经冲动的化合物,使它们有别于其他具有芳香风味的物质。因此,它们具备气味(鼻前:通过鼻孔;或者鼻后:通过连接嘴鼻的鼻后窝)、风味,以及刺激三叉神经(辛辣,新鲜…)。[4]

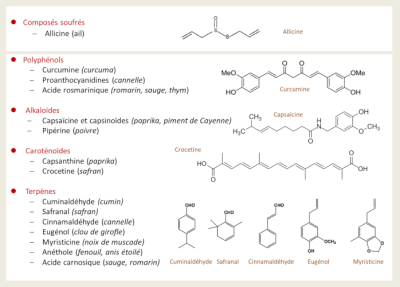

香草和香料没有营养价值 ,但富含生物活性化合物 、多酚、生物碱、萜类和类胡萝卜素[5]。所有这些物质都具有让植物更好适应环境的特性(图4)。

这些植物内部的次级代谢物,对热、细菌或病毒应激具有保护作用。例如,姜黄粉中的姜黄素类化合物,以姜黄素最广为人知,其是当植物受到侵犯,改变信号通路并诱导抗氧化和抗炎防御的首要保护。这一机制普遍存在于植物界。通过将香料添加到食物中,我们也可以从这些特性中获益。

1.4 香草和香料–膳食抗氧化物质的来源

一茶匙牛至;80g葡萄;一茶匙肉桂;250ml石榴汁;

香草和香料的抗氧化能力[6]很高[7](图5)。例如,一茶匙干牛至的抗氧化能力相当于80克葡萄,而一茶匙肉桂的抗氧化能力相当于250毫升石榴汁。烹饪前在肉中加入香草和香料的混合物,可以防止对人体细胞有害的脂肪氧化衍生物[8]的产生。沙拉调料中含有的香草可以使食物抗氧化能力提高一倍[9]。需要指出的是,与维生素不同,香草和香料中的多酚类物质具有抗干燥和耐热的特性。

2. 香草和香料可减少盐、糖和脂肪,并增加蔬菜的摄入

选择不健康的食物会增加罹患营养相关性疾病的风险,如肥胖、II型糖尿病、高血压、炎症、癌症或最近研究发现的肠道菌群改变和失调(阅读 人类微生物群:我们健康的盟友)。

因此,正确选择食物是公众健康问题的关键, 然而这一目标很难达到。尽管国家营养与健康计划(PNNS)在2001年至2017年间相继开展了众多针对普通大众的营养宣传活动,最新食品消费调查显示绝大多数人的蔬菜摄入量仍然太少,而脂肪、盐和糖的摄入过多。

然而,人为干预研究告诉我们,定期食用香草和香料有助于纠正这些饮食错误 。

2.1 香草和香料可以减少盐的摄入

过量的盐(图6)是导致高血压、心血管疾病和胃癌的罪魁祸首。降低盐的摄入量一直是国家营养和健康计划(PNNS)的重点 目标。因此,第三期国家营养和健康计划(2011-2015)制定了食盐摄入量指标:男性8克/天、女性和儿童6.5克/天,比法国人均食盐摄入量降低20%。

最近发表的研究表明,使用香草和香料能有效减少盐的摄入量。在每日饮食中加入香草和香料6个月后,盐的摄入量和尿钠排泄量会显著减少[10]。另一项试验中,参与研究的受试者对咸味的感知受到了辣味的影响 ,使他们在保持味蕾愉悦的同时减少了盐的摄入量。临床上,参与者 血压也显著降低[11]。最后,一份最近的英文报告显示 ,与工业生产的咸味汤[12]相比,在含盐量少53%的汤中添加香草和香料能够提高汤的接受度和可口性。

吃“味道丰富”的食物有助于广大读者减少盐的摄入,仍然能保证可口性,还能预防高血压。

2.2 香草和香料可以增加蔬菜的摄入

增加水果和蔬菜的摄入是营养推荐 的重点(图7)。尽管法国进行了多次的 宣传活动,但水果和蔬菜的消费量仍然停滞不前。口味是人们选择蔬菜的首要动机,而健康或控制 体重通常并非首选。在一项针对超重者的干预试验中,这些受试者的蔬菜摄入量很少( 但吃辛辣 食物和使用烹饪香草会增加他们的蔬菜摄入量;对平时不喜欢吃蔬菜的受试者最明显,他们的蔬菜摄入量增加了91%[13]。

对年轻受试者的营养教育很重要,几项针对儿童[14]和高中生[15]的研究表明,在食物中添加香草和香料有助于他们食用不喜欢的蔬菜(芹菜和南瓜)并选择健康的食物。

2.3 香草和香料使人们更容易吃低脂、低糖食物

超重和肥胖的流行 主要归因于过量的脂肪和糖的摄入量,尤其是大量饮用软饮料 (图8)。对美国超重志愿者进行的两项研究表明,用草药 和香料调味的低脂、低糖食品的可口性更好,而如果不在相同的食品中添加香草和香料,其可口性变差[16],[17] 。

3. 香草和香料–预防营养性疾病的盟友

Neuroprotection神经保护;Protection cardiovasculaire心血管保护;Cancers癌症;Microbiote微生物群;Inflammation炎症;Insuline regulation du glucose胰岛素调节葡萄糖;Controle du poids控制体重;Epices et herbes香料和香草

鉴于营养性疾病的发病率不断增加,香草和香料的潜在生物学和临床学收益成为非常活跃的研究焦点[3,4](图9)。大部分这类研究聚焦于评估香料和香草对肥胖、心血管疾病、炎症疾病以及营养不良的影响。

3.1 香草、香料和肥胖

按一定营养剂量定期使用某些香料,可以控制体重,主要通过三种机制:增加能量消耗、提高生热作用和激活脂肪燃烧代谢。

最常提及的香料是富含辣椒素[18]的红椒粉 ,以及富含姜辣素和姜烯酚[19]的姜。必须强调的是,超过享乐的营养剂量(即提供味觉快感的营养剂量)是危险的。因为过量的类辣椒素会刺激肠胃、改变肠道渗透性,并伴有烧灼感,从而导致肠胃失调。

3.2 香草、香料和胰岛素抵抗:从代谢综合症到II型糖尿病

在法国,超过五分之一的人患有代谢综合症,即前期糖尿病,特征包括腹部肥胖、高血压、血胆固醇和甘油三酯过高、高血糖和胰岛素抵抗[20]。代谢综合症使人们面临II型糖尿病、心血管疾病和早期认知能力下降的高风险。

科学已证实,某些香料(肉桂、姜黄、小茴香 、丁香和小豆蔻,图10)和地中海草本植物(月桂、龙蒿、迷迭香)可以调节血糖,增加胰岛素敏感性,改善代谢综合征的生物标志物[21]、[22]、[23]。特别需要指出的是,每天食用一克肉桂粉就足以将患有代谢综合征的受试者的血糖水平降至生理值[24]。

3.3 香草、香料和心血管疾病

在法国,心血管疾病是导致死亡的首要原因, 往往源于营养 问题(过量摄入盐、糖以及饱和脂肪),并伴有高胆固醇血症、高甘油三酯血症、氧化型低密度脂蛋白 高血压和血管功能障碍。

对心血管疾病的预防而言,富含有机硫化合物[25]的大蒜效果最明显。经常食用大蒜粉(600 毫克/天)或鲜蒜(2.7 克/天)可降低胆固醇水平、减少血小板聚集,起到降压作用[26]。

经常食用小豆蔻、芫荽、姜黄、生姜和丁香(图11)也有助于预防心血管疾病。如上所述,这些香料可以通过抗氧化和抗炎效应抵御代谢综合症及其对血管的影响。

此外,在保护血管内皮细胞方面,姜黄的潜在作用似乎不仅限于其抗炎和抗氧化的特性,还因其能诱导具有血管扩张和降低聚集性作用的[27]。

3.4 姜黄、生姜和炎症性疾病

姜黄和生姜能阻断促炎症细胞转录因子的激活和炎症脂质介质的产生。

生姜中(图12)富含姜辣素和姜稀酚,连续每天食用 ,可以显著减轻慢性肌肉疼痛[28]。

姜黄(图13)及其活性成分姜黄素是强效的抗炎药,几个世纪以来一直被印度阿育吠陀医学认可[29]。然而,姜黄粉的生物利用度非常差[30],降低了其有效性,因此需要以10克/天左右的高剂量使用。姜黄素的特性已被众多国际研究证实。以500毫克/天的姜黄素治疗关节炎的效果,与非甾体类抗炎药(NSAIDs)一样有效[31]。

3.5 香草、香料和微生物群:未来

这是一个非常有前途 的研究领域。饮食是影响肠道微生物组成,以及我们健康的主要因素。

近期,一些体外和体内研究表明,膳食中的多酚类化合物会影响肠道菌群的丰度 和特性。含多酚类化合物的食物(茶、可可和水果)可以减少致病菌的数量,增加有益的双歧杆菌和乳酸杆菌的数量。在此情景下,7种香料和香草的混合物(牛至、迷迭香、姜黄、黑胡椒、辣椒、肉桂、生姜)具有类似益生元效果 ,为预防和治疗肠道失调及肠道通透性障碍 开辟了广阔的前景[32]。

4. 香草、香料和健康:益处与局限

益处:科学研究证实,定期食用香草和香料对我们的健康有诸多益处。

香草和香料:

- 通过防止食物氧化和致癌化合物的形成来提高食物的营养品质;

- 帮助养成健康的饮食习惯:少盐、少糖、少脂肪,多吃蔬菜;

- 凭借其抗氧化、抗炎和增强胰岛素效用的特性,可预防:肥胖,心血管疾病,代谢综合症和II型糖尿病, 炎症性疾病,以及最近被证明的肠道失调。

局限:

- 无副作用的有效每日剂量仍然需要依靠经验判断 ,需要进一步的干预研究来更好地确定有效剂量;

- 不应低估农药和重金属的污染风险。根据欧洲法律,食用不可追溯的进口草药和香料是危险的。

- 一般来说,种植香料只需要很少的杀虫剂和除草剂。在储存过程中有可能被细菌或微生物污染,造成中毒风险 。因此,控制生长条件、贮藏条件和分析质量是必需的。

这些局限性并没有质疑香草和香料本身对人类健康的益处,但凸显了信息不完备的危险性。

5. 要点

- 烹饪中经常使用香料和香草不仅是为了愉悦味蕾,还可以让我们收获健康的饮食习惯,而且还能作为营养成分参与非传染性疾病的营养预防。

- 然而,由于香草和香料在疾病预防中的最佳剂量和作用机制尚未完全清楚,仍需要开展进一步的临床研究。

参考资料及说明

封面图片:香料市场。

[1] Bruno Jarry, Spices. Hachette Pratique Publisher, 2007

[2] HCSP: Pour une politique nutritionnelle de Santé Publique en France (PNNS 2017-2021). September 2017.

[3] Hubert Richard, Spices and Aromatic Herbs, Planet-Vie, Wednesday, April 30, 2008, https://planet-vie.ens.fr/article/2061/epices-herbes-aromatiques

[4] http://www.reseau-education-gout.org/association-reseau-gout/IMG/pdf/dossier-mecanismes-degustation-jan12.pdf

[5] Opara E.L. & Chohan M., 2014, Culinary herbs and spices: their bioactive properties, the contribution of polyphenols and the challenges in deducing their true health benefits. Int. Mol. Sci. 15(10):19183-202.

[6] 氧化应激是与氧气产生反应的物种(例如自由基)对我们机体细胞的攻击。生活方式、环境因素和饮食是暴露于攻击我们细胞的氧化应激的主要风险因素。在香料和草药中发现的几种植物营养素是抗氧化剂,具有防止自由基引起的有害连锁反应的特性。

[7] Yashin A., Yashin Y., Xia X. & Nemzer B., 2017, Antioxidant activity of spices and their impact on human health: A review. Antioxidants (Basel) 6(3).pii:E70; doi:10.3390/antiox6030070.Review.

[8] Li Z., Henning S.M., Zhang Y., Zerlin A., Li L., Gao K., Lee R.P., Karp H., Thames G., Bowerman S. & Heber D., 2010, Antioxidant-rich spice added to hamburger meat during cooking results in reduced meat, plasma, and urine malondialdehyde concentrations. Am..J Clin. Nutr. 91:1180-4

[9] Ninfali P., Mea G., Giorgini S., Rocchi M. & Bacchiocca M., 2005, Antioxidant capacity of vegetables, spices, and dressings relevant to nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 93(2):257-266

[10] Anderson CA, Cobb LK, Miller ER, Woodward M, Hottenstein A, Chang AR, Mongraw-Chaffin M, White K, Charleston J, Tanaka T, Thomas L, Appel LJ. Effects of a behavioral intervention that emphasizes spices and herbs on adherence to recommended sodium intake: results of the SPICE randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015; 102(3):671-9

[11] Li Q, Cui Y. Enjoyment of spicy flavor enhances central salty-taste perception and reduces salt intake and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2017; 70(6):1291-9.

[12] Ghawi SK, Rowland I, Methven L. enhancing consumer liking of low salt tomato soup over repeated exposure by herbs and spice seasonings. Appetite. 2014; 81:20-29

[13] Li Z. et al, Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2015, 6,437-444

[14] Savage JS, Peterson J, Marini M, Bordi PL, Birch LL. The addition of a plain or herb-flavored reduced-fat dip is associated with improved preschooler’s intake of vegetables. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013; 113(8):1090-5

[15] D’Adamo CR, Mc Ardle PF, Balick L, Peisach E, Ferguson T, Diehl A, Bustad K, Bowden B, Pierce BA, Berman BM. Spice my plate: nutrition education focusing upon spices and herbs improved diet quality and attitudes among urban high school students. Am J Health Promot.2016; 30(5):346-56

[16] Peters JC, Polsky S, Stark R, Zhaoxing P, Hill JO. The influence of herbs and spices on overall liking of reduced fat food. Appetite 2014; 79:183-8

[17] Alcaire F, Antunez L, Vidal L, Gimenez A, Ares G. Aroma-related cross-modal interactions for sugar reduction in milk desserts: influence of consumer perception. Food Res Int. 2017; 97:45-50.

[18] Varghese S., Kubatka P. & Rodrigo L., 2016, Chili pepper as a body weight- loss food. Int J Food Sci Nutr. Nov29: 1-10

[19] Wang J., Ke W., Bao R. & Chen F., 2017, Beneficial effect of ginger Zingiber officinale Roscoe on obesity and metabolic syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1398(1):83-89

[20] Insulin resistance: decreased sensitivity to insulin. As liver, muscle and fat cells become resistant to insulin, higher and higher amounts of insulin are needed to ensure that glucose enters the insulin-dependent cells, less glucose enters these cells and remains in the blood.

[21] Bi X., Lim J. & Henry C.J., 2017, Spices in the management of diabetes mellitus. Food Chem 217:281-93;

Fatemeh Y., Siassi F., Rahimi A., Koohdani F., Doostan F., Qorbani M. & Sotoudeh G., 2017, The effect of cardamom supplementation on serum-lipids, glycemic indices,and blood pressure in overweight and obese pre-diabetic women: a randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Metab. Disord. Seven 29:16-40.

[22] Bower A., Marquez S. & de Mejia E.G., 2016, The health benefits of selected culinary herbs and spices found in the traditional mediterranean diet. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 56(16:2728-46)

[23] Akilen R., Tsiami A., Devendra D. & Robinson N., 2012, Cinnamon in glycaemic control: systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Nutr. 31(5):609-15.

[24] Bradley J.M., Organ C.L & Lefer D.J., 2016, Garlic-derived organic polysulfides and myocardial protection. J Nutr. 146(2):403S-409S

[25] Warshney R. & Budoff M.J., 2016, Garlic and heart diseases J Nutr. 146(2), 416S-421S

[26] Rastogi S., Pandey M.M. & Rawat AKS. 2017, Spices: Therapeutic potential in cardiovascular health. Curr Pharm Des. 23(7):989-998

[27] Campbell MS & Fleenor BS, 2017, The emerging role of curcumin for improving vascular dysfunction: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. doi 10.1080/10408398-2017.1341865

[28] -Nahaim A, Jahan R & Rahmatullah M., 2014, Zingiber officinale: a potential plant against rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis 159089.doi 10.1155/2014/159089

[29] Basnet P & Skalko-Basnet N., 2011, Curcumin: An anti-inflammatory molecule from a curry spice from inflammatory pathologies to cancer. Molecules 16(6):4567-98

[30] Bioavailability is defined as the fraction of the administered dose of active ingredient that reaches the systemic circulation and the rate at which it reaches the systemic circulation.

[31] Chin KY, 2016, The spice for joint inflammation: anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in treating osteoarthritis. Drug Des Develop Ther. Seven 20. 10:3029-3042.

[32] Lu QY, Summanen PH, Lee RP, Huang J, Henning SM, Heber D, Finegold SM & Li J., 2017, Prebiotic potential and chemical composition of seven culinary spice extracts. J Food Sci. Jul 5. Doi:10:1111/1750-3841;13792

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: ROUSSEL Anne-Marie (2024年3月9日), 香料和香草:对我们的健康有什么好处?, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年3月30日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/sante-zh/spices-aromatic-herbs-benefits-health/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。