《南极条约》:环境与科学的独特治理

《南极条约》是世界对致力于和平、科学和环境保护区域进行国际治理的独特范例。该条约诞生于1957-1958年国际地球物理年末,随后又有各种议定书对其加以补充,其中包括《环境保护议定书》,即《马德里议定书》。该议定书或许是对南纬60度以南区域的准入条件和活动影响最大的文件。议定书中最广为人知的一项规则是暂停开采南极洲的矿产资源。与许多媒体报道所宣称的不同,在2048年暂停该禁令的可能性不大。不过,在起草适用于南极大陆的未来规则时,需要考虑到气候变化或旅游等活动的影响,这是在起草《南极条约》的创始文件时所没能考虑到的。[1]

1. 南极条约:乌托邦的实现

1.1. 在什么情境下签署了该条约?

[资料来源: 美国铸印局。由厄文·梅特斯(Ervine Metzl)设计。[公共领域],维基共享]

1957-1958年,国际地球物理年(IGY)聚集了来自67个国家4,000个组织的25,000多名科学家,吸引了全世界对南极洲科学考察的关注(图1)。第二次世界大战之后使用的新型技术工具,特别是火箭和无线电通信领域的新技术手段得到了应用。国际地球物理年活动的成功证明,地球存在一个没有党派利益和商业贪婪的地方。在那里,人类活动只是为了科学研究。《南极公约》是一个政治意义上的实验,其主要目的只有一个:确保南极洲能够继续专用于和平目的,避免成为国际争端的场所或对象。必须承认的是,除了南大洋的海洋资源外,严酷的环境几乎没有为这第六大洲留下开发的余地,这一承诺几乎没有产生任何地缘政治后果。

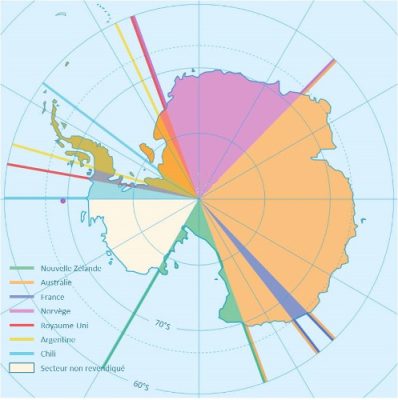

[资料来源: © Yves Frenot, IPEV]

这很可能就是七个所谓的“属地”国(即声称拥有该大陆部分领土的国家,包括阿根廷、澳大利亚、智利、法国、新西兰、挪威和英国,见图2)以及美国、苏联、日本、比利时和南非于1959年12月1日在华盛顿(图3)签署《南极条约》的原因。该条约于1961年6月23日生效。

1.2. 《南极条约》讲了什么?

首先,南极洲只允许和平活动。因此,该条约禁止一切具有军事性质的措施(第I条)及核爆炸。禁止在该地区处置放射物(第五条)。

[资料来源:赫尔曼·弗莱格(Herman Phleger) (http://www.teara.govt.nz/files/37206-pc.jpg)[公共领域],维基共享]

其次,该条约使南极洲成为一个致力于科学的大陆,在这里每个缔约国可以在该大陆上任何一个它希望的地方自由建立研究站。该条约鼓励通过研究人员交流和免费提供科学成果来开展科学合作(第二条和第三条)。

再次,该条约冻结了领土主张。换句话说,它没有要求7个“属地国”放弃前已提出过的对在南极洲的领土主权的权利或要求,而是要求他们不要提及南极洲的领土主权的要求。同样,该条约防止任何进一步的领土主权要求(第四条)。

最后,《南极条约》适用于南纬60度以南的整个地区,没有预定的末端。

1.3. 谁是该条约的缔约国?

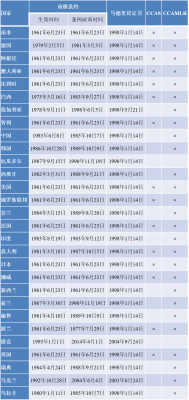

该条约目前有53个缔约国,包括29个所谓的“协商缔约国”,这些国家在南极开展科学考察后,获得了投票权(表1)。所有这些国家每年都召开南极条约协商会议(ATCC),交流信息并向本国政府提出建议,以促进条约目标的实现。

1.4. 支持《南极条约》的其他协定书

[资料来源:© IPEV]

其他议定书逐渐丰富了《南极条约》,共同构成了南极条约体系:

- 《保护南极海豹公约》(CCAS [2],伦敦,1972年)禁止猎杀这些动物(图4)。

- 《南极海洋生物资源保护公约》(CCAMLR[3],坎培拉,1980年)规定对南大洋界限(南纬50°左右的南极极地前沿)以内的广阔地理区域的渔业资源进行评估与管理(图5)。

图5. 如阿德利地(Terre Adélie)海岸海床的繁荣景象所示,虽然南极洲的陆地生物多样性贫乏,但海洋生物多样性却非常丰富。

[资料来源: © Erwann Amice, IPEV]

图6. 南极洲是地球上仅存的相对未受人类直接影响的地方。

[资料来源: © Gaetan Quere, IPEV]

2. 《马德里议定书》与环境保护

2.1. 议定书及其附件: 人类活动的严格准则

[资料来源:《南极条约》秘书处(www.ats.aq)]查阅关于《条约》秘书处保存的最新表格,请访问https://www.ats.aq/devAS/ats_parties.aspx?lang=f

《南极环境保护议定书》是地球上其他地方所没有的治理工具,它规定了适用于南极洲所有活动的原则,以确保这些活动尊重环境。

从一开始,该议定书就有四个补充附件,规定了适用于南极洲人类活动的基本原则和约束性规则,涉及环境评估、动植物保护、废物管理和防止海洋污染。2002年增加了关于特别保护区管理的第五个附件。2005年通过了第六个附件,其中规定了环境损害的责任制度。第六个附件只有在所有缔约国批准后才能生效。

更具体地说,这些附件中的一些内容表明了加入《马德里议定书》的国家努力尽量减少人类活动对南极洲影响的精神。

-

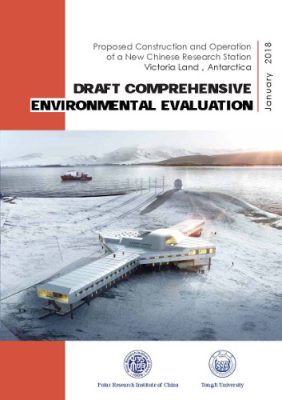

图7. 中国于2018年编制的关于在维多利亚陆地建设新研究站的EGIE项目。环境保护委员会和《南极条约》协商会议于2018年5月在布宜诺斯艾利斯审议了该EEIG项目。 附件一规定,在《条约》区域内开展的任何活动必须首先接受环境影响评估。如果人们认为这种影响“至少是轻微的或暂时的”,该活动必须得到国家主管当局(在法国是法属南部和南极领地最高行政长官)的授权。如果估计预期影响 “超过轻微的或短暂影响”,则需编制一份详细的影响研究报告(EGIE [4]),并在国际层面上公布和评估(图7)。这一影响评估和许可程序至关重要,因为它是监管《条约》区域内活动的唯一工具。然而,该条约也存在不足之处:概念模糊,定义不清。这些概念在不同的国家可以有不同的解释。

图8. 在1911年的南极探险中,斯科特带上了小马和雪橇犬。事实证明小马完全不适合,雪橇犬也不足以帮助他完成任务。他不如竞争对手阿蒙森准备得充分。现在,《马德里议定书》附件二禁止将此类动物带进南极。

[资料来源: Herbert G. Ponting[公共领域],通过维基共享]

该附件还规定,可以将特别受威胁的南极物种列入“特别保护物种”名单。迄今为止,只有罗斯海豹(Ommatophoca rossii)具有这种地位。由于长期过度捕猎,海豹一直濒临灭绝的边缘,2006年才从名单中删除(图9)。

图9. 在19世纪和20世纪初,海狮几乎被捕猎者灭绝。它们主要因为皮毛而被猎杀。在停止捕猎后,海狮的数量迅速增长,2006年不再被列为特别保护物种。

[资料来源: © Gildas Lemonnier, IPEV]- 附件四禁止船只在海上排放未经处理的石油、有害物质、垃圾或废水。

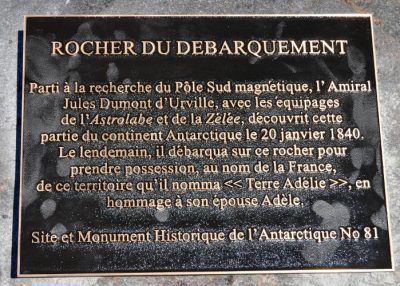

图10. 纪念朱尔斯·杜蒙·居维尔发现南极洲的牌匾。该牌匾放置在称为“D-Day Rock”的小岛上,在阿德利地上构成南极历史遗址和第81号纪念碑。

[资料来源: © TA60, IPEV]

2.2. 环境保护委员会

《马德里议定书》设立了一个特别机构——环境保护委员会(CPE),就环境状况和为确保环境保护而应采取的措施向RCTA提供意见。环境保护委员会由已加入《议定书》的国家代表(2017年为39个,见表1)以及三名常驻观察员组成:

图11. 2017年在北京召开的环境保护委员会第20次会议上的委员会成员

[资料来源:南极条约秘书处图像库]- 国家南极局局长理事会(COMNAP),

- 和南极海洋生物资源养护委员会(CCAMLR)。

[资料来源: © Peter Convey, British Antarctic Survey]

可以邀请其他国际组织或非政府组织作为专家提供技术或科学咨询。

每年,环境保护委员会(CPE)与RCTA会晤(图11)。议题广泛,商讨出许多建议(非约束性)或措施(约束性),这些建议或措施现对成员国具有约束力,并规范包括科学家在内的南极访客的日常生活。EPC目前设定的优先事项主要涉及:

- 了解气候变化对南极陆地和海洋环境的影响,以及至少在局地范围对这些影响可能采取的应对措施。

- 自然或意外引入的非本土物种对南极生物多样性带来的风险(图12)。

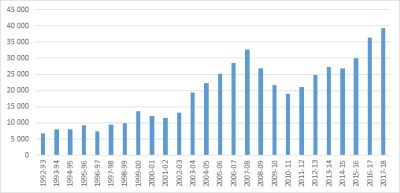

图13. 1990年代初至今,由船只运送并在南极洲登岸的游客数量变化情况。每年11月至3月间有近4万名游客访问第六大洲,其中科学家和相关后勤人员却不到7,000人。

[资料来源: IAATO数据[5] 2017-http://www.ats.aq/documents/ATCM40/ip/ATCM40_ip163_rev1_e.doc; author edited graph]- 保护南极洲陆地和海洋大型生态系统的代表性区域(与南极海洋生物资源保护委员会合作保护海洋大型生态系统)。

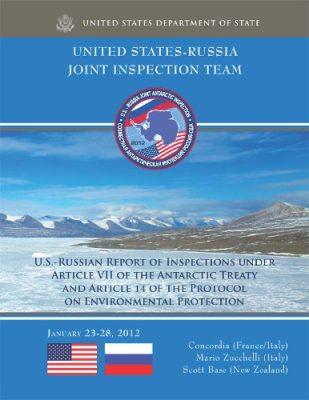

2.3. 检查——监测遵守情况的工具

[资料来源: © 《南极条约》秘书处: http://www.ats.aq/documents/ATCM35/att/ATCM35_att069_e.pdf](译者注:United States Department of State 美国国务院;United States-Russia Joint Inspection Team 美俄联合检查小组;U.S.-Russian Report of Inspections under Article VII of The Antarctic Treaty and Article 14 of The Protocol on Environmental Protecion 美俄根据《南极条约》第七条和《环境保护议定书》第十四条撰写的检查报告)

为确保《南极条约》和《马德里议定书》的规定得到遵守,缔约国可以任命观察员随时自由进入考察站及其设施,搭乘前往南极洲的船只和飞机。经征求有关国家的意见后,这些视察报告(图14)将提交给环境保护委员会和RCTA审议。虽然这些检查工作长期以来一直与政府科研站有关,但现在它们越来越多地针对依赖私营运营商的旅游船只或货运。

2.4. 矿产资源开发——让我们直说2048年后的真相

在《马德里议定书》的条款中,最广为人知的是关于暂停开采矿产资源的规定 (第7条):“禁止除科学研究以外的任何与矿产资源有关的活动”。但这也是最容易被媒体误解的条款,媒体普遍错误地宣称,在2048年《议定书》生效50年后,暂停开采矿产资源的这一规定将失效。

事实上,同《南极条约》一样,《马德里议定书》的条款没有规定终止日期。不过,其第25条规定,经各协商缔约国一致同意,可随时对《议定书》进行修正,或在50年后,缔约国如有此意愿,可要求在特定会议上讨论该问题。各缔约国通过和批准的程序颇为繁琐,需要四分之三的缔约国(包括1991年的所有缔约国,当时为26个国家)批准,拟议的修正案方能生效。

换言之,《议定书》的起草者为确保其稳健性采取了预防措施。2048年之后《议定书》的内容发生变化的可能性微乎其微,恢复矿产资源的开采更是几乎不可能的事。

3. 南极海洋生物资源养护委员会:渔业资源和海洋保护区

[资料来源: By Uwe Kils I am willing to give the image in 1700 resolution to Wikipedia Uwe Kils[CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) 或 GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons]

虽然矿产资源被明令禁止开采,但南极洲还有其他资源——海洋生物资源正在被开采。为了应对人们对磷虾日益增长的商业利益需求以及对几种海洋物种的过度开发,南极海洋生物资源养护委员会于1982年成立,目标是保护这些资源。委员会现有25个成员国(24个国家加上欧盟)和11个加入国。这些国家承诺遵守《公约》的规定,但尚未签署或批准《公约》。该公约适用于南极点以南的所有鱼类、软体动物、甲壳动物和海鸟种群[6](图15)。南极海洋生物资源养护委员会采用基于生态系统的管理方法,不禁止开采,但前提是开采必须以可持续的方式进行,并考虑到捕捞对生态系统其他组成部分的影响。

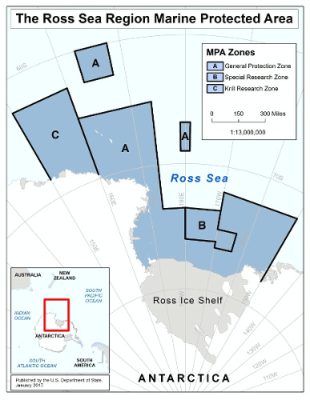

[资料来源: © U.S. Department of State. OES/OPA.2017年1月.https://www.state.gov/e/oes/ocns/opa/ross/index.htm]

2009年,第一个公海海洋保护区(MPA)启动。该保护区位于南奥克尼群岛南部高原,面积94,000平方公里。南极海洋生物资源养护委员会继续提议对其他海洋保护区(MPAs)进行分类。2016年10月,成员国一致同意了美国和新西兰关于建立世界上最大海洋保护区的提议。该保护区位于罗斯海,面积为155万平方公里。一些活动将受到限制,以实现特定的养护、栖息地保护、生态系统监测和渔业管理目标 (图16)。全球海洋保护区的72%将成为“禁捕”区,禁止一切捕捞活动。其他地区则允许捕捞鱼类和磷虾,但只能用于科学研究目的。关于其他分类提议的谈判正在继续,其中一个项目是由法国和澳大利亚牵头的南极洲东部项目。

4. 科学研究,公认的南极价值

南极洲自被发现以来,一直是科学发现取之不尽用之不竭的宝库。这里集中了当前社会关注的所有问题: 气候变化、臭氧消耗、生物多样性侵蚀等。南极半岛可能与北极地区一样,是对全球变暖最敏感的地区: 过去50年间南极半岛的气温上升了2到4摄氏度。这直接影响到海洋的食物资源,再加上磷虾捕捞管理不善,导致了在这一领域一些鸟类数量减少(图17)。

[资料来源: © Clotilde Dubois, IPEV]

气候变化会导致冰川消退或漂浮在大陆边缘的冰架破裂。根据政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)的报告,南极洲冰川加速流动可能会导致未来几年全球海平面上升。

《马德里议定书》特别承认南极洲的这一科学价值,该议定书关于特别保护区的附件五规定,任何区域,包括任何海洋区域,均可被指定为“南极特别保护区”,以保护其突出的环境、科学、历史或美学价值,或大自然的野生状态,或保护正在进行或计划进行的科学研究。

5. 单一治理,但它经得起时间考验吗?

[资料来源: © Philippe Apelt, IPEV]

因此,《南极条约》及其相关议定书提供了一个独特的国际法律体系。该体系自创建以来,经过不断改进,运作良好。这就表明各国有可能就科学研究或环境保护等崇高目标达成一致(图18)。但是,由于决策建立在共识的基础之上,因此在一些重大问题上,如管理旅游活动、建立新的研究站、创立海洋保护区,要取得快速进展并非易事。某些在南极洲行为谨慎的国家的崛起,比如中国,正在不断增加其在整个南极洲的研究基础设施的数量,并毫不犹豫地公开使用诸如“利用南极洲”(RCTA 2017年在北京)等表述,未来也可能在某种程度上扰乱这一非典型治理的既定游戏规则。南极条约体系的工具作用及其目前的运作模式是否足够强健以应对这些新的压力,未来将见分晓。

参考资料及说明

封面照片:12月繁殖季节结束时阿德利岛上的帝企鹅。[来源: © Alain Mathieu,IPEV]

[1] 本文是对同一作者发表在Revue Australe et Polaire第82期上的一篇文章的补充。该文章于2017年12月由AMAEPF出版 (http://www.amaepf.fr/)

[2] CCAS – 保护南极海豹公约

[3] CCAMLR – 南极海洋生物资源养护委员会

[4] EGIE – 全球环境影响评估

[5] IAATO – 国际南极旅行社协会

[6] 鲸目动物由1946年签署的《国际捕鲸管制公约》审议。该公约是在《南极条约》制定之前签署的。因此,国际捕鲸委员负责处理南大洋鲸鱼问题。

环境百科全书由环境和能源百科全书协会出版 (www.a3e.fr),该协会与格勒诺布尔阿尔卑斯大学和格勒诺布尔INP有合同关系,并由法国科学院赞助。

引用这篇文章: FRENOT Yves (2024年3月13日), 《南极条约》:环境与科学的独特治理, 环境百科全书,咨询于 2025年1月22日 [在线ISSN 2555-0950]网址: https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/zh/societe-zh/antarctic-treaty-unique-governance-for-environment-and-science/.

环境百科全书中的文章是根据知识共享BY-NC-SA许可条款提供的,该许可授权复制的条件是:引用来源,不作商业使用,共享相同的初始条件,并且在每次重复使用或分发时复制知识共享BY-NC-SA许可声明。